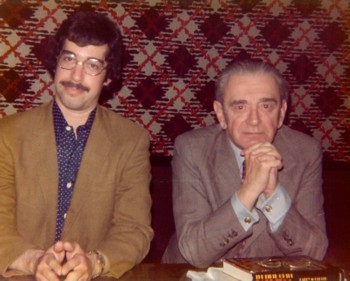

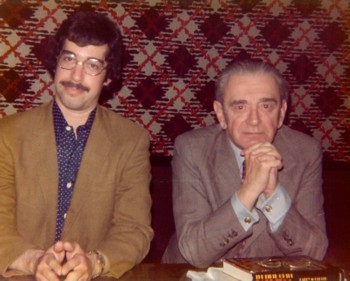

Author Steve Vertlieb and Miklos Rozsa, 1979 |

If Herrmann brought brilliance and sensitivity to his musical scoring, Rozsa brought passion, power, and romantic longing. He has inspired many with his works.

Unlike the flamboyant Herrmann, Rozsa was a quiet, humble and cultured gentleman who often appeared shy and thoughtful.

A consummate musician, Rozsa hadn't the slightest interest in composing music for the movies. Rather, he was a most serious young man who couldn't conceive of writing serious music for the motion picture screen. |

It was his impression that fox trots were the standard assignment for composers of early sound films, and that he could never bring himself to write such music. Here was a composer of enormous integrity and explosive, passionate expressiveness. He was born for the concert halls of the world, and not a darkened movie theatre.

April 18th, 1907

Born April 18th, 1907, in Budapest, Hungary, Rozsa discovered a love for music from his mother who had studied as a classical pianist. When he was five years old his great Uncle Lajos embarked on a sojourn to Paris, and asked the precocious little boy what he wanted his uncle to bring back for him. The boy replied, "Bring me a violin--not a toy, but a real one." Uncle Lajos complied and brought back a real violin. It wasn't long before the five year old was learning to play the instrument. At the age of seven he performed Haydn's Toy Symphony, playing first violin and conducting a small orchestra. At about that time he began composing his own short orchestral pieces. One of his earliest works was titled "Student March."

The Rozsa family estate was located North of Budapest in the village of Nagylocz, within the county of Nograd. It lay at the foot of the Malta Mountains, an area largely inhabited by the Paloc, an indigenous Magyar people who lived in the region. Their original folk music and songs fascinated the boy, forming the dramatic impetus of a style that would influence his own creativity for the rest of his creative life.

In 1925, at age eighteen, he completed his formal schooling. His father wanted him to study chemistry at the University of Budapest, but the boy rebelled. Despite his father's insistence that he study in a field in which he might realistically make a living, Miklos was determined to study music. It remained his first and only love. He left home and journeyed to Leipzig where, as part of a compromise agreement with the elder Rozsa, he studied both chemistry and music. Mendelssohn, who had also taught at the school, had founded the Conservatory.

Chemistry studies were held at the University. On his way each day to the University, Rozsa passed the great musical publishing house of Breitkopf & Hartel. The growing conflict between chemistry and music eventually took an emotional toll on the struggling student and in September 1926, the elder Rozsa succumbed to his son's persuasions, allowing him at last to abandon his chemistry studies and enroll in the music Conservatory full time.

|

In 1927, while a student at the Conservatory, Rozsa composed his first great success at the request of his teacher, "Opus 1, A String Trio". Soon after, he wrote his second successful composition, the "Quintet For Piano And Strings". The second work was brought to the attention of Karl Straube, an extremely influential Professor at the school, who brought the twenty one year old student to a meeting with his friends at the oldest musical publishing house in Germany. After gazing in wonder each day at the imposing structure on his way to the University, and to his utter astonishment, both pieces were purchased by the firm of Breitkopf & Hartel.

While Rozsa continued his studies, and before his graduation from the Conservatory, his picture appeared within the pages of Breitkopf and Hartel's distinguished quarterly magazine. It wasn't long before German orchestras were performing the early works of the young artist.

Upon his graduation, Rozsa began teaching younger students in order to supplement his income. His music, however, was quickly becoming more adventurous and he was advised to leave Leipzig, where the disturbing rise of Nazism might prevent free expression. |

The Nazis, it seemed, regarded anything other than traditionalism as rabble rousing, and unpatriotic. Paris, at the time, was a haven for burgeoning artists.

Paris

Rather than become stifled and strangulated by the unyielding restrictions to creativity imposed with disturbing frequency by the Germans, Rozsa decided to leave Germany for more fertile fields of experimentation. Arriving in Paris in the Spring of 1931, Miklos Rozsa was a mere twenty four years old and, like most everyone during this period of cultural renaissance, eyes wide with wonder, he was astonished and exhilarated by the flourishing artistic freedom. Yet, while artistic freedom and creativity were nurtured and often cherished, financial reward remained miniscule unless one's name was recognized.

One night at dinner with Arthur Honegger, Rozsa asked his friend how he was able to make a living at composing. Honegger replied that he supported his family by writing music for films. Astonished, Rozsa found it difficult to believe that his esteemed friend could lower his standards to write miniscule melodies and popular songs. Honegger assured him that the music he composed for the cinema was of the highest quality, and that he would never have lowered his standards. Honegger advised his young friend to go to the theatre and see the film presentation of Les Miserables

Both the film and its music were dramatic and lyrical. Impressed, Rozsa telephoned Honegger to tell him that the music he had written for the film was as good as anything he had ever committed to paper, and that he should create a suite from the score. The young artist felt instinctually that this was a medium rife with possibilities, and that he might also be induced to compose a work for the screen.

Honegger promised to recommend Rozsa the next time his own schedule became too hectic to take on a new project. Not long after that, Rozsa received an invitation to tea from French director, Jacques Feyder, whom he knew socially. Feyder asked Rozsa to sit at the piano and improvise material based upon his ideas of animated sequences such as "uproar" music, and people running. At the completion of this unexpected exercise, Feyder smiled and said, "That tells me everything."

Meanwhile, Rozsa's financial difficulties were mounting and he needed something more than vague promises of future employment. A Hungarian writer named Akos Tolnay whom Rozsa had met was working in England on a screenplay for a film called Sanders Of The River. Discussing his young friend's economic woes, Tolnay suggested that he come to England where he might find more opportunities for employment. Rozsa was persuaded, arriving in London in 1935. Language was to present a formidable problem, as he could speak only Hungarian and French. Meanwhile, Tolnay was experiencing difficulties of his own.

He had now formed his own production company, Atlantic Films, but couldn't seem to get his first independent project off of the ground. He wanted American actor, Edward G. Robinson, for a leading role but had to go to America in order to negotiate with Warner Bros. to secure his services. Rozsa was promised the assignment as composer but, so far, there was no film.

Many of his symphonic works were being recognized and performed internationally, but infrequent royalty payments weren't enough to live on. Shortly after that, Rozsa read in the newspapers that his friend, Jacques Feyder, was in London for a visit. He telephoned the director at his hotel to tell him how deeply he had admired his film, La Kermesse Heroique. Feyder was having lunch with his wife and some friends, and invited Rozsa to join them.

Marlene Dietrich

At lunch he was introduced to an elegant German couple, Mr. and Mrs. Sieber. Sitting between Feyder and Mrs. Sieber, the conversation remained amiable, if innocuous. Suddenly, Mrs. Sieber turned directly to Rozsa and asked him if her song was ready. At a loss for words, Rozsa stammered that it wasn't quite finished, but that he was diligently working on it. Feyder had apparently told the lady that Miklos Rozsa was writing the music for their picture, and that she would have a song to sing. Incredulous, Rozsa turned to the director and whispered, "Who is she?" Feyder turned white and whispered back "Idiot...it's Marlene Dietrich."

Knight Without Armor, Robert Donat and Marlene Dietrich |

Apparently, Dietrich had liked Rozsa and gave her approval to the director. Now all they had to do was to convince Alexander Korda at Denham Studios that the composer, who had never scored a film, was the right choice to write the music for Feyder's film with Dietrich. Feyder, who had once been an actor, offered a bravura performance when Korda objected that Rozsa was an unknown quantity.

"What do you mean that you've never heard of Miklos Rozsa?" he protested.

"Why, Rozsa is one of the greatest composers of the age."

Korda acquiesced, not wishing to irritate Feyder, and agreed to sign Rozsa as the composer of Knight Without Armour for London Films.

|

Meanwhile, Tolnay had returned to London and began preparations for his film with Edward G. Robinson, Thunder in the City. Tolnay invited Rozsa to the set watch a screen test with a young girl he was interviewing for a part. It was the first time that Rozsa had ever been on a film set. The girl was red headed, and radiantly beautiful.

Rozsa felt certain that she would win the part, but the director remarked to him that she wasn't photogenic and he dismissed her. A short time later she flew to Hollywood for another screen test and, as Greer Garson, became a star at MGM.

Knight Without Armor

Production began on Knight Without Armour and Rozsa, despite the best intentions, was at a loss as to how to start. After all, he had never written music for a film. Consequently, when he composed a frantic scherzo for full orchestra to illustrate a quiet family tea on the ancestral lawn, Feyder had to take him aside and gently explain that only soft background music would do justice to the dialogue and the tenor of the moment. Under Feyder's intelligent direction, Rozsa learned to develop his craft.

For a scene in which a group of Russian officers stand around a piano singing, as Princess Alexandra (Dietrich) enters the room, the pianist was unaccounted for. Feyder asked Rozsa to put on a Russian uniform and play for the cameras. Rozsa argued that he wasn't an actor, to which Feyder replied "You don't have to act...just play." Rozsa dutifully consented, donned a uniform, and performed the piano recital. He wouldn't appear before the cameras again until 1970, conducting "Swan Lake", in Billy Wilder's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, although his back can be seen briefly, conducting Rachmaninov, in The Story of Loves (MGM, 1953).

After his debut film work in Knight Without Armour, Rozsa was asked by Zoltan Korda to write the score for his first big picture, the classic Victorian tale of disgrace and heroism, The Four Feathers. Filmed earlier for Paramount in 1928 by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, and starring Richard Arlen and Fay Wray, The Four Feathers tells the epic story of a British soldier drummed out of the service for cowardice. Abandoned by his family and friends, he infiltrates enemy lines posing as an Arab, enduring torture and dismemberment in order to save his regiment.

Photographed in Technicolor on location in the Sudan, and starring Ralph Richardson, John Clements and June Duprez, Korda directed the picture while suffering the effects of malaria. Genuinely ill during the difficult shoot, he could often been seen behind the camera with a thermometer dangling from his mouth. When recording of the score began, Rozsa and conductor, Muir Mathieson, welcomed Queen Mary to the sound stage. Visiting the scoring sessions, Her Majesty arrived on the set with her lady in waiting, and Alex Korda. The picture premiered on April 20th, 1939, at the Odeon, Leicester Square, and enjoyed tremendous critical and commercial success. The author, A.E.W. Mason, appeared at the opening and delivered a short speech for the much-heralded event.

|

Alex Korda had his biggest hit to date with The Four Feathers, and approached Rozsa about composing the score for another film in preparation at the studio. It was an Arabian nights fantasy based rather loosely on the silent Douglas Fairbanks classic, The Thief of Baghdad. The difficulty was that the existing script was in turmoil, and a director had yet to be assigned. Korda finally settled on a choice for his director, Dr. Ludwig Berger, who had recently filmed Les Trois Valses in Paris. Korda liked the picture and thought that Berger might be a good match. |

|

The music for the French film had been written by famed operetta composer, Oscar Straus, and Berger insisted that his friend write the music for The Thief of Baghdad. Korda had promised the assignment to Rozsa, but feared losing his newly found director. Still, he advised Rozsa to sit tight. As far as he was concerned, Rozsa was the right composer for the Technicolor fantasy. As music by Straus began arriving from Vichy, Korda grew increasingly agitated. The music was, as Rozsa later recalled, "Impossible...typical turn of the century Viennese candy-floss." Ever the gentleman, Rozsa bided his time and said nothing. Muir Mathieson, however, was infuriated; telling anyone who would listen that the songs by Straus would ruin not only the picture but the studio, as well.

Alex Korda summoned Rozsa and Mathieson to his office, along with Dr. Berger. In a theatrical tirade worthy of Barrymore, Korda berated the pair with the stern admonishment that in all creative matters, Berger was solely in charge. Berger grinned happily, while Mathieson stormed out of the office in a rage. After Berger had gone, Korda motioned for Rozsa to come closer to his desk. Korda chuckled triumphantly. It had all been an act for the director's benefit.

|

|

Korda instructed Rozsa to begin writing his own music for The Thief of Baghdad, but to keep it a secret from Berger and Mathieson.

He asked Rozsa simply to trust him. By now Rozsa had learned the language, both the English language and the language of the British film industry. He knew that Alex Korda had formulated a shrewd scenario. A week later he had completed his score. Excitedly, he telephoned Korda's office to report his progress. "Do you want to hear it," he asked. "No," Korda replied. "I want to set you up in an office next to Dr. Berger's.

| "I'll supply you with a piano, and I want you to play your score on that piano as loudly as you can every day." Rozsa obliged and began playing his score as loudly as possible. This went on for days. He'd begin playing at ten in the morning, and stop at around five in the afternoon. On the third day, Berger burst into the room demanding to know just what Rozsa was up to. Rozsa explained that he simply had a few ideas for the picture and was working on them.

Berger said that there was no need for Rozsa's music--that Oscar Straus was hard at work writing his own score for the picture. Still, Berger was curious and asked to hear what Rozsa had written. Despite his objections, Berger found himself liking what Rozsa had played for him. As the day wore in he had listened to the entire score. |

|

Pacing the floor nervously, Berger excused himself. Ten minutes later he returned, telling Rozsa that he had just seen Korda. He admitted that he enjoyed Rozsa's music much more than what Straus had written and that he wanted to replace Straus with Rozsa.

Korda sent a telegram to Straus informing him that his services were no longer required. Straus cabled back that his reputation was being ruined, and that he would have no recourse but to sue Korda. Korda offered to pay him in full for his efforts, however, and Straus reluctantly accepted his offer.

As there were to be songs in the film, sung either as solos and performed by the title character or as lilting lullabies, lyrics were needed to illustrate the melodies that Rozsa had written. At Korda's "suggestion," the lyrics would be written by his friend, Sir Robert Vansittart, chief diplomatic advisor to the British Foreign Office. Vansittart, a poet and lyricist, was also the Grey Eminence...the power behind the throne at the Foreign Office. Additionally, Vansittart co-authored the script for the picture with character actor, Miles Malleson, who also played a significant part in the film as the childlike Sultan and father of the beautiful princess. (In later years, Malleson would work for Hammer Films, most memorably in Horror of Dracula and The Hound of the Baskervilles.)

Work on the picture progressed far more slowly than had been hoped. Eventually, both Michael Powell and Tim Whelan were brought in to co-direct the film with Dr. Berger. Key sequences had yet to be realized, and it was decided that the flying sequence with Rex Ingram as the Djinn would have to be shot in America in the Grand Canyon. All of the cast and crew, including Rozsa, were ordered to the states in order to wrap up production. Rozsa anticipated spending, perhaps, forty days in Hollywood. It became, however, his principal residence for the remainder of his life.

Upon completion of the picture, Rozsa finished writing the final elements of his score. Muir Mathieson was required to conduct the music for the soundtrack. Rozsa vowed that henceforth he would conduct his own music for films. The Thief of Baghdad was premiered on Christmas day, 1940, both in Britain and in America and remains one of the most gloriously imaginative films ever made, the equal of The Wizard of Oz in each of its Technicolor frames. The musical scoring by Rozsa, set to a visual tapestry of genies, wizards, flying horses and magically airborne carpets, is among the most wondrous of his career and a landmark in symphonic scoring for films.

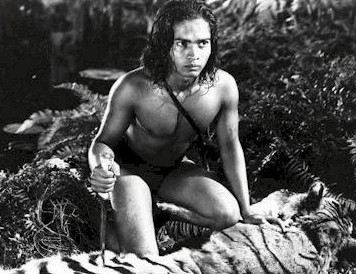

Rozsa had loved Rudyard Kipling's stories since his boyhood, so when Zoltan Korda called upon his services once more to write the music for The Jungle Book, he was elated. The young Indian actor who had starred in both Drum and The Thief of Baghdad for the Kordas would star once again as Mowgli, the wolf boy. Sabu had been "discovered" by documentary director, Robert Flaherty, in the stables of the Maharajah of Mysore and brought back to London in something of the fashion in which Mowgli was brought to civilization from the jungle.

|

Sabu, ever naive and charming, suggested to Rozsa that they might become millionaires by traveling from town to town astride the elephant the boy had recently purchased. Sabu would sing to passers by atop the elephant, while Rozsa would ride beside him conducting an orchestra.

The Jungle Book, while not in the same class as the earlier Arabian Nights fantasy was, nonetheless, a beautiful and haunting film, easily towering over its many remakes over the years. However, its most striking element remains Rozsa's exquisite score. |

After their success with the recordings of Prokofiev's "Peter and the Wolf", featuring a spoken narration, RCA Victor offered Rozsa an opportunity to record his Jungle Book Suite in much the same fashion. Sabu would perform the narration and the album was recorded in New York with Miklos Rozsa conducting Arturo Toscanini's famed NBC symphony orchestra.

The Jungle Book became the first American film score to be recorded and released commercially by a major record label, a fact which RCA Victor capitalized on heavily during their advertising campaign for the release. "Song of the Jungle", Rozsa's miraculous invocation of the dense jungle and its inhabitants slowly awakening to a new day, has been recorded and performed countless times and is still a staple of concert halls and international orchestral programs.

Five Graves To Cairo

Margaret Finlason, a former actress and secretary/companion to Gracie Fields, arrived at a dinner party at the home of June Duprez one night in Hollywood. She and Rozsa had met previously when she had been employed at Denham Studios in London, where she would sit by the scoring stage and listen to his music. They became reacquainted at the Duprez dinner party and were married in August 1943. At about that time Rozsa received a telephone call from his agent, notifying him that Paramount wanted him for Five Graves To Cairo, to be directed by Billy Wilder.

Rozsa met with Wilder and his associate, Charles Brackett, and formed an immediate bond with both men. Wilder told Rozsa that if he liked his work on Five Graves To Cairo, then he would most certainly be his first choice to score their next picture. Rozsa ran into resistance, however, from the head of Paramount's musical department who found his work overly dissonant and harsh, and not in keeping with classical Hollywood romanticism. Wilder prevailed, and Rozsa's music remained in the finished picture.

In November 1943, conductor Bruno Walter offered four performances of Rozsa's "Theme, Variations and Finale" at Carnegie Hall in New York. The fourth performance was to be broadcast live over the radio but when Walter became ill he handed the baton to one of his young assistants who conducted the piece.

Rozsa thought the broadcast performance exhilarating, and superior to the earlier ones conducting by Walter. The performance earned critical raves, both for the music and for its youthful conductor, Leonard Bernstein.

|

Billy Wilder was hard at work on his newest film, a story based upon a novel by James M. Cain called Double Indemnity. True to his word, Wilder offered the picture to Rozsa who wrote a searing score for the steamy Film Noir classic with Fred MacMurray, Barbara Stanwyk and Edward G. Robinson.

When it came time to record the score, Rozsa was verbally assaulted by the same Paramount music head that had previously voiced his dislike for the music in Five Graves To Cairo. The executive lost his pomposity quite unexpectedly when Wilder approached the pair and explained in drooling sarcasm that, unlike the esteemed studio head, he loved what Rozsa had written for the picture.

The executive, attempting to recover what little was left of his face, later summoned Rozsa to his office where, in front of his lip-serving assistant, admonished Rozsa that "music for Carnegie Hall had no place in films." Rozsa further infuriated the executive by taking obvious pride in his illiterate "reprimand." |

In conversations with David O. Selznick, Alfred Hitchcock remarked that he had been impressed with the score for Double Indemnity and would like Rozsa to write music for the new psychological thriller he was preparing with Ingrid Bergman and Gregory Peck. When he accepted the assignment in 1945, he was deluged with the notorious Selznick memos in which the producer instructed him at every turn how to compose and orchestrate the music. Selznick even had his secretary telephone Rozsa to inquire how many violins had been utilized for the main title sequence. He had counted the precise number of violins used by Franz Waxman in his previous production and asked Rozsa to re-record the main title theme upgrading the violin section to the exact number that Waxman had used.

|

Rozsa respectfully obliged, adding a fascinating instrument he had been wanting to use for years. And so Spellbound became the first motion picture ever to use the Theramin, an instrument widely associated with science fiction films (The Thing From Another World, 1951, Dimitri Tiomkin), for its strange and chilling implication of Gregory Peck's supposed madness as Dr. Edwards.

Although the "Spellbound Concerto" became Rozsa's most performed and recorded concert work, Alfred Hitchcock seemed less than pleased with the completed score. He never employed Rozsa again, but evidently found what he needed in the inspirations of Dimitri Tiomkin and, later, Bernard Herrmann. Nonetheless, the "Spellbound Concerto" remains a popular and enduringly beautiful staple of concert halls across the world after sixty years. |

The Lost Weekend

When Selznick learned that Rozsa had used the Theramin once again in his next picture for Billy Wilder at Paramount, he flew into a rage and asked his secretary to telephone him. Selznick felt that the use of the Theramin for the first time in Spellbound made both the instrument and its sound unique and that, somehow, its use in another picture was a betrayal of Selznick and his film. Angered by the telephone accusations, Rozsa slammed down the receiver..but not before announcing that he had indeed used the offending Theramin, along with the violin, the trumpet, the triangle and the piccolo, and that the Theramin was not the property of David O Selznick.

The Lost Weekend was the terrifying tale of an alcoholic whose lust for the bottle nearly destroys his life and the lives of everyone around him. Cast horrifyingly adrift in a sea of faceless pedestrians and liquor store clerks one unforgettable weekend in Manhattan, Ray Milland must find agonizing salvation in the elusive, yet numbing serenity yielded by a single shot of whiskey.

His escalating panic, stumbling across Third Avenue in blind ambition, turns to emotional hysteria as he realizes that the dry strangulation clutching his throat will not be comforted...his raging thirst will not find peace--for it is Yom Kippur, and all the shops along his path have closed in observance of the Jewish holiday.

For this memorable sequence, Rozsa constructed an unforgettable musical nightmare, haunted by the mocking screams of the lonely Theramin. Ray Milland won an Oscar for his powerful portrayal of the tormented writer. While Rozsa's score did not share that distinction, he had to have found a degree of satisfaction in learning that the music that won the coveted trophy was his own score for Hitchcock and Selznick, Spellbound. Jerome Kern, in partnership with Cole Porter and the Gershwin estate, through his publishing arm, Chappell's, printed the orchestral suite from Spellbound, making it accessible to music lovers in profusion.

The Gangster's Cycle

Former New York columnist-turned-producer Mark Hellinger set up his own production company at Universal and, in 1946, began a brief, three-film association with Rozsa that would usher in the next phase of his career in Hollywood. Beginning with The Killers, which introduced Burt Lancaster to the screen, and continuing with Brute Force (1947) and The Naked City (1948), the Hellinger films constituted the composer's gangster cycle.

The gritty, uncompromising scores were unyielding testaments to the passionate anger of society's invisible souls. Brute Force, in particular, stands out as one of the composer's most striking dramatic scores, but The Killers will forever be remembered as the music that "inspired" Walter Schumann to adapt its familiar four-note theme as his signature for television's Dragnet television series. The uncredited piece became identified in later years, through judicial judgments, as Rozsa's, thereafter insuring joint credit for both men. When Mark Hellinger died of an apparent heart attack, Rozsa assembled a tribute to his friend, a powerful suite comprised of themes from each of the three films they had worked on together. It later became known, in subsequent recordings, as "Background To Violence".

In 1947 Rozsa wrote his brilliant, frightening score for the independently produced, low budget quasi-horror film, The Red House. A disturbing murder mystery surrounding a mysterious Red House, buried deep within forbidding woods, starred Edward G. Robinson as a deranged farmer who buries the secrets of a hidden past in a rotting, abandoned cabin, obscured and hidden by the demented leaves and sheltering trees of a terrible forest inspired by Red Riding Hood and her demented sojourn. The score, eerily reflective of innocence lost and its journey into darkness, is at once wondrous and exhilarating, childlike and brooding, wondrous and terrifying, a breathtaking masterpiece of imaginative composition.

A Double Life

In 1948, Rozsa returned to Universal to compose the music for A Double Life, the story of an actor so consumed by the intensity of his roles that he becomes the character he's portraying. When he stars as Othello on Broadway, it drives him to the brink of madness and murder.

Ronald Colman starred in the leading role, while George Cukor directed. Like the story and its ever altering sub plots and themes, Rozsa's theme music was complex and daring, capturing both worlds in mere moments of dramatic encapsulation. The front office balked at his interpretation and, after enthusiastic "previews," demanded that it be changed. When Cukor heard of it he told Rozsa "If you change one note, I'll kill you."

Cukor's instincts were, as usual, correct for Rozsa went on to win his second Oscar for the score of A Double Life. The driving "theme" of the picture, a story of a man leading two lives, must have influenced Rozsa significantly for, in 1982, when he authored his autobiography summarizing the dual careers of a composer leading two lives, one in Hollywood and one on the concert stage, he called it A Double Life.

Rozsa moved over to Metro Goldwyn Mayer in 1949, soon scoring Madame Bovary for director, Vincente Minnelli. It was a happy collaboration for both director and composer, and the film was well received. Rozsa's golden era for the studio began, however, in 1951 with the first of his acclaimed biblical epics, Quo Vadis. His contract with the studio allowed him first refusal on MGM's most prestigious efforts, as well as the clout to request any production that may have interested or intrigued him.

Directed by Mervyn LeRoy, the film today is regarded more as an historical curiosity than a quality production. In many ways, its a virtual remake of Cecil B. De Mille's 1932 film, The Sign of the Cross, though not nearly as entertaining. And yet, Rozsa found his association with the picture a deeply moving experience, laying the groundwork for several more significant films to follow. Visiting Rome, he, as well as other cast members, were granted an audience with the Pope. A visit to the Sistine Chapel also affected him profoundly.

In researching authentic music and instrumentation of the period, he was able to create a remarkably effective score. The love theme from Quo Vadis, "Lygia", was recorded by RCA Victor and sung by perhaps the greatest operatic voice the world has ever known, Mario Lanza. While this was the only time that Lanza recorded Rozsa's music, it wasn't the only time that they had worked together.

| On July 24th, 1948, Miklos Rozsa conducted the Hollywood Bowl Symphony Orchestra for a special "MGM Night At The Hollywood Bowl." The concert evening included live performances by Mario Lanza, and Kathryn Grayson, and featured a reading by Lionel Barrymore. The studio-sponsored event was broadcast that evening over NBC Radio.

The following year produced two more richly scored pictures, Plymouth Adventure and the heroic romance, Ivanhoe. |

|

Ivanhoe

Ivanhoe, once again featuring Robert Taylor, this time far more effectively, was a wonderful knights in shining armor tale, based upon the classic novel by Sir Walter Scott.

Rozsa's intoxicatingly romantic accompaniment invites provocative witness to Rebecca's forbidden love for Sir Wilfred of Ivanhoe. 1953 was, by the composer's own description, one of the most joyously productive of his life.

Writing some of the most beautiful music of his career for such film productions as Julius Caesar, The Story of Three Loves, All The Brothers Were Valiant, Knights of the Round Table (once more with Robert Taylor) and the magnificent Young Bess, he also found time to fulfill a commission from violinist Jascha Heifetz, during his three month summer vacation. The resulting "Concerto For Violin and Orchestra" remains the most exultant, exquisite composition of Rozsa's career. It would find renewed life some years later beyond traditional concert halls.

Julius Caesar was a bittersweet assignment for Rozsa. Producer John Houseman had wanted his friend, Bernard Herrmann, to write the music for the picture. As Herrmann was under contract to 20th Century Fox at the time, and Rozsa was himself bound to a handsome contractual obligation at MGM, Herrmann was denied the job. Rozsa disliked having to replace a composer he not only admired, but also regarded as a friend. For his part, Herrmann was sincerely disappointed by the studio's decision. To his enormous credit years later, when preparing to conduct an album for London Phase 4 of "Great Shakespearian Film Music", Herrmann chose as one of his selections a suite from Julius Caesar by his friend, Miklos Rozsa. Such was the musical integrity of the man.

During the early 1950s when childrens' television was beginning to come into its own, George Reeves donned a flaming red cape and ascended, suspended by wires, into television history as the man of steel in The Adventures of Superman.

Little of the music, other than its popular theme, was actually written for the series. Most of it, derived from "stock" music hired for the purpose (usually from the Capital Cue library), was repeated simultaneously, on infinite numbers of programs. One particular piece of music remembered from the series seemed to stand apart from the others, a thrilling and frenzied moment of unforgettable symphonic escapism, borrowed inexplicably from a source unrelated to the derivative library, and associated usually with runaway robots and the like.

Just how this queer musical extract found its way to children's television remains a mystery. Its actual title is "Allegro molto agitato e tumultuoso," and was written in 1933/1934 for a concert work titled "Theme, Variations And Finale". Its composer was, of course, Miklos Rozsa, who was blissfully unaware of its presentation on early television until we spoke of it at a film conference in Bloomington, Indiana in 1979.

The world premiere of the "Concerto For Violin and Orchestra" was presented on January 15th, 1956, in Dallas, Texas with Walter Hendl conducting the Dallas symphony orchestra, and Jascha Heifetz performing the violin solo. Later that year, Heifetz, Hendl and the orchestra reprised their performances for the brilliant recording by RCA Victor's Red Seal label. Rozsa's artistic renewal, meanwhile, continued to flourish in 1955 with his exquisite themes for the historical drama, Diane, starring Lana Turner.

|

After the somewhat painful experience of Julius Caesar, Rozsa was to work with producer, John Houseman, once more but this 1956 production would be a far happier experience. Vincente Minnelli was preparing his film of Irving Stone's bestseller on the tragic life of Post-impressionist painter, Vincent Van Gogh, and Rozsa was delighted to have been offered the film. His relationship with Minnelli, a deeply sensitive artist himself, was a fruitful one and Rozsa relished the opportunity to paint in music what Van Gogh had attempted on canvas.

Kirk Douglas delivered, perhaps, the dramatic performance of his career as the tortured painter and Rozsa mined the psychological torment of this lonely, brooding genius with understanding and complexity. His music is at once tender and mournful, passionate and beautiful, a powerful symphonic dissection of an excruciating existence. Rozsa's portrait of the brotherly love between Vincent and his adoring sibling, Theo, is deeply explored and exquisitely expressed. The score is, quite simply, among the most passionate of the composer's career, a symphonic love letter to a tragic artist too emotionally fragile to endure the uncontrollable suffering of his heartbreaking Lust For Life. |

Ben Hur

In 1959 Rozsa wrote a stark, impressive theme for MGM's apocalyptic science fiction tale of the last three people alive after a nuclear holocaust devastates the earth, The World, The Flesh, and the Devil. His next work would become, perhaps, the most significant and monumental of his long career. William Wyler was among the most important directors in Hollywood and so the studio was elated when he accepted their offer to helm their most important picture since Gone With The Wind. Ben Hur was a massive production that would either make or break the legendary company.

Indeed, when producer, Sam Zimbalist, left Hollywood for locations in Rome he was told, "the future of MGM is in your hands." The stress of that responsibility ultimately cost him his life when, during production, he suffered a fatal heart attack. Wyler, though a great director, had acquired a reputation of being difficult to work with. Rozsa had been warned of his possible interference in the creation of the music and approached the director with a degree of trepidation. In discussions with Wyler on how to approach the Nativity sequence, the director suggested that we hear "Adeste Fideles" on the soundtrack to indicate to the audience that this was, in fact, the first Christmas.

Rozsa reminded Wyler, somewhat delicately, that "O Come All Ye Faithful" was an eighteenth-century tune. Rozsa created his own lovely lullaby to serenade the infant Jesus. When Wyler grimaced in displeasure, Rozsa calmly handed him the baton. Wyler got the message and politely left the scoring stage. For all the expense, wringing of hands, and fatality, Ben Hur would become one of the most prestigious and honored films in motion picture history. Rozsa's score is indescribably gorgeous, magnificent, wondrous, and unforgettably beautiful.

It is, arguably, the crowning achievement of his career in films. The picture went on to earn eleven academy awards, including Best Picture, Best Director and, for Miklos Rozsa, his third Oscar for Best Music. The picture went unchallenged in its Oscar glory until the release of James Cameron's epic film of the doomed ocean liner, Titanic, in 1997 nearly forty years later.

Rozsa continued mining the richly fertile fields of his historical and biblical inspirations with King of Kings in 1960, and El Cid in 1961. King of Kings, the Samuel Bronston remake of the silent classic by Cecil B. De Mille, proved a problematic venture, an international co-production with too many hands groping the filmic pot.

Rozsa essentially "found his voice" in the goodness and spiritual artistry that lay deep within his own heart. One has only to listen to his interpretation of "The Lord's Prayer" to recognize that the beauty of the music came less from Bronston's troubled visualization of Christ's time on Earth, than from the purity of Rozsa's creative integrity.

El Cid

El Cid, however, was another matter entirely. Working for Samuel Bronston once more, this was a sweeping, romantic and tragic chapter of Spanish history brilliantly realized by Rozsa in his epic musical masterpiece. El Cid, wonderfully enacted by Charlton Heston, is a noble knight committed at all costs to preserving his homeland from the ravages of rampaging, would be conquerors.

His passionate, enduring love for Sophia Loren must find finality in self-sacrifice and ultimate death and yet, like Jesus in King of Kings, virtually rises again to free the humble peasants whose lives he was sworn to protect. Rozsa's scoring of El Cid, exhaustively researched and inspirational, is a superb listening experience, the composer's enduring testament to the honor and heroism of a noble soul. With Ben Hur, El Cid reflects the consummate artistry of Rozsa's own musical nobility, constituting the very peak of his creative career.

In 1963 CBS Television aired a rare tribute to the world of film music with a memorable concert featuring Bernard Herrmann, Dimitri Tiomkin, Franz Waxman, John Green, Alfred Newman and Miklos Rozsa conducting their scores before a live audience. While the actual televised performance appears lost forever, the Columbia Records CD of concert highlights lives on.

The V.I.P.'s, in 1963, was Rozsa's last score for MGM. Enjoying only moderate success, the Richard Burton/Elizabeth Taylor tearjerker provided Rozsa with yet another opportunity to explore the opulence of his rich, romantic expressiveness. His "Overture" and "Love" themes are unimaginably haunting. It was the end of an era....

Rozsa had not been asked to write a score in five years. During that time he had decided to devote the remainder of his life to the composition of works for the concert stage. However, out of nowhere came a telephone call from friend and fellow Hungarian, George Pal. Rozsa liked Pal, as did most everyone. The gentle producer/director of such films as The Time Machine and War of the Worlds was working on a new science fiction picture at MGM called The Power and asked Rozsa if he would consider returning to the studio in order to score his picture.

The Power

Rozsa agreed to help Pal bring the project to fruition. The completed production was, however, confusing, silly and ineffectual. Pal told me years later that the studio had rushed The Power into production months before it was scheduled to shoot because another production had been cancelled and they needed something to fill the proverbial void. Pal was terribly disappointed by both the realization of, and reception to the film. The one element he did cherish, though, was the experience of working at last with Miklos Rozsa. Rozsa delivered a unique, powerful score, which far surpassed the quality of the meager science fiction film it was written for. Pal liked the music so much that for years he held onto the original tapes of the score in his private collection.

|

Billy Wilder re-entered Rozsa's life in 1970. One of Wilder's preferred methods of relaxation while preparing his film scripts was to listen over and over again to the "Concerto for Violin and Orchestra". It was one of his favorite pieces of music. He would tell Rozsa repeatedly that one day he would find use for the concerto in one of his films. Well, now he had chosen that film and wanted Rozsa to adapt his concerto for the picture, as well as compose additional music. Rozsa had always been happy to work with Billy Wilder. Both shared enormous respect and affection for the other. The film was, perhaps, Wilder's most personal production and his last masterpiece, The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes. |

Robert Stephens as Holmes delivered a sensitive, vulnerable, quite fragile performance as the master detective and Rozsa's second movement of the violin concerto became a most haunting and memorable love theme for Holmes and his cautiously shielded broken heart.

The film, originally three hours in length, was butchered by United Artists who wanted a product running under two hours. Flawed and compromised as it is, Wilder's Sherlock Holmes is a tender, unforgettably romantic take on Arthur Conan Coyle's famed consulting detective.

The Golden Voyage of Sinbad

In 1973 Rozsa worked with legendary filmmaker, Ray Harryhausen, on the belated sequel to The 7th Voyage of Sinbad, a classic fantasy film which had been scored by Bernard Herrmann. Harryhausen was, himself, an enormous fan of classic film music and was delighted to secure the talents of Miklos Rozsa for The Golden Voyage of Sinbad. For Rozsa, although he found Ray Harryhausen charming and musically literate, his experience on the film was not a terribly happy one.

Producer Charles Schneer was trying to cut costs at every turn and hired a very small number of musicians to record the soundtrack. The per diem Italian musicians played often ineptly and appeared to care little for their craft. Consequently, Rozsa's adventurous score sounds at times ill-served and insufficient. His admonishments to the members of the hired orchestra went virtually unheeded, and he was frequently enraged by the spectacle of musicians reading newspapers, rather than studying their music. "You call yourselves religious? Well, music is our religion," he would tell them. The lecture, however, was futile.

|

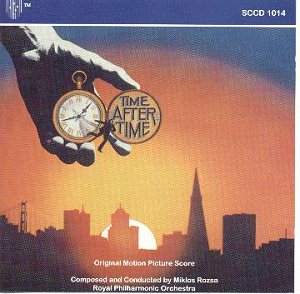

Toward the end of the decade, Rozsa began enjoying an artistic renaissance on screen with some fine films from a variety of youthful, caring directors. The best of these came in 1979 with the wonderful Time After Time, a Nicholas Meyer science fiction/romantic fantasy which joined H.G. Wells and Jack The Ripper in a race against, and through time. Time After Time is a joyous film with a lovely, sensitive performance by Malcolm McDowell as Herbert George Wells, and a gorgeous score by Rozsa. The little film was a triumph for all concerned. That same year saw the release of a marvelous Hitchcockian thriller directed by Jonathan Demme entitled Last Embrace, featuring a rich, romantic score by Rozsa. |

In 1980 WQED Television, in cooperation with the Pittsburgh Symphony, presented a memorable tribute to the art of motion picture music as part of its on going series, Previn & The Pittsburgh. The program, telecast across the country over public broadcasting, featured fascinating conversation, anecdotes, and live performances of classic film music. Sharing their observations, along with their music, were Andre Previn and his guests, John Williams and, in a very rare television appearance, Miklos Rozsa.

Just two more motion picture assignments remained...a war time thriller called Eye of the Needle in 1980 and Rozsa's gallant au revoir to the movies, Dead Men Don't Wear Plaid, the latter a very clever Carl Reiner tribute to the dark Film Noir detective thrillers of the 1940s, many of which had originally been scored by Rozsa. By time the scoring sessions had been scheduled, however, Rozsa was sidelined with a bad back ailment. Composer Lee Holdridge conducted the soundtrack sessions of Rozsa's score. It was the first time since the early days for Korda in London that Rozsa hadn't conducted his own music.

Health

In September 1982, Rozsa suffered his first stroke, leaving him paralyzed down his left side. He lived quietly in the years left to him. He continued to compose and, on April 18th, 1987, he turned eighty years of age. There were many tributes on radio and on stage. The Mayor of Los Angeles declared it "Miklos Rozsa Day." That same month he was presented with a Life Achievement Award at the ASCAP Film and Television Music Awards dinner. His tribute that evening was presented by his friend and colleague, Billy Wilder. His health further deteriorated, however, with additional strokes robbing him of his cultured speech.

Nearly blind at the end, he was visited often by those whose lives he had touched. Composer David Raksin, was a frequent visitor to the Rozsa home atop a winding hill on Montcalm Avenue. On the imposing gate at the entrance to the residence in the Hollywood Hills there was an impressive "R" for Rozsa, not unlike the bold "K" upon the entrance to Xanadu that housed and protected Charles Foster Kane from the world that lay beyond.

In the early days of summer, 1995, Rozsa suffered yet another stroke, enduring the final weeks of his existence on life support at the Hospital of the Good Samaritan in Los Angeles. Finally, on July 27th, 1995, the composer succumbed to pneumonia and passed quietly from this earth. He was eighty-eight years old.

The 100th Anniversary

High on the list of nominated scores is the work of Miklos Rozsa. April, 2007 marked the 100th anniversary of Miklos Rozsa's birth and, among the countless honors, tributes and recordings commemorating the centennial were an evening of performance held at the Hungarian Embassy in Washington, DC, hosted by the Hungarian Ambassador; a superb premiere recording of the composer's brilliant score for Billy Wilder's The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes for Tadlow Records, a Grammy nominated recording of the Concerto For Violin and Orchestra and Sinfonia Concertante performed by violinist Anastasia Khitruk, a series of concerts and lectures held in Belgrade, and a momentous nine day film festival...the first ever held in the United States...screening seventeen motion pictures scored by the composer, and attended by daughter Juliet Rozsa and her children, Nicchi and Ariana.

Beginning December 26th, 2007 and culminating on January 3rd, 2008, the remarkable festival at San Francisco's venerable Castro Theater featured presentations by the city's Mayor, proclamations from the Hungarian Ambassador to the United States, live organ performances of the composer's scores performed by David Hegarty, and an on stage interview with Juliet Rozsa. On the musical heels of its outstanding success with The Private Life of Sherlock Holmes, Tadlow Records has recorded a triple disc CD presentation of Miklos Rozsas monumental score for El Cid scheduled for release in the Fall of of 2008.

Perhaps, the proclamation from the Hungarian Embassy, written for the San Francisco film festival at the Castro Theater, captured the essence of the composer's influence and legacy most eloquently when they wrote:

"On behalf of the grateful people of Hungary, on the centennial of his birth,

let me express the pride and pleasure we take in commemorating the life

and work of Miklos Rozsa. This distinguished composer, and native Hungarian,

brought pride and recognition to his people through the art and artistry of his talent,

giving noble voice, through the medium of motion pictures and on the concert stage,

to the rich legacy and fertile tradition of Hungarian culture. In a musical career spanning

sixty years, Miklos Rozsa achieved honor for his people, and recognition by his peers,

winning three richly deserved Academy Awards and sixteen Oscar nominations from the

Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, for his significant contribution to the sound

of movies.

In joyous tribute to both the man and his music, we join Miklos Rozsa's family and his

Millions of admirers around the world, in presenting this proclamation from the Hungarian

People, honoring one of our greatest composers and children, on the occasion of his

one hundredth birthday, and the first comprehensive film festival ever held in the United

States, initiated and presented by San Francisco's historic Castro Theater, honoring his

wondrous, and enduring, musical legacy."

Dr. Ferenc Somogyi,

Ambassador of Hungary to the U.S.

In 1968 this writer enjoyed the uncommon privilege of meeting, and then befriending Miklos Rozsa. It was a distinct honor, during the last twenty-seven years of his life, to think of him as a friend--and having known him remains one of the greatest joys, and profound treasures of my own life.

|