| David Schecter and Kathleen Mayne are the producers of the Monstrous Movie Music series of re-recordings which feature a wealth of classic music from many of everyone's favorite science fiction, horror and fantasy films. Concentrating primarily on the 1950s, they have lovingly crafted five albums (so far) with the intent of faithfully reproducing the musical sound of these neglected musical masterpieces. Their efforts are of great importance in the world of film music since this music has generally been considered unimportant and, therefore, been unavailable as stand alone recordings. |

|

| Monstrous Movie Music: www.mmmrecordings.com/index.html

1) Monstrous Movie Music

2) More Monstrous Movie Music

3) Creature From the Black Lagoon

4) Mighty Joe Young

5) This Island Earth |

It is also a matter of economics and many record labels are understandably unwilling to expend the time, energy, and money on an album release that, in all likelihood, will appeal to a very small segment of the music buying public. All the more reason to thank David and Kathleen--probably the only husband and wife team with their own label devoted exclusively to this genre music--or taking the time and devoting the considerable energy and money towards fulfilling many film music lovers' dreams. |

We spoke to David Schecter upon the release of the two latest Schecter/Mayne discs, This Island Earth (and other alien invasion films) and Mighty Joe Young (and other Ray Harryhausen animation classics).

| How did you and Kathleen Mayne become associates in these endeavors?

|

We happened to meet at a film music class, where Kathleen's teacher Ernest Gold (Exodus, It's A Mad, Mad, Mad World, and Inherit the Wind) was making a guest appearance. We swapped talents (I showed her some of my humor writing, and she let me listen to some of her compositions), got to know each other, fell in love, got married, and now we find ourselves with a film music label. We refer to our five releases as our "five babies."

|

| What are some of the challenges facing an independent record producer?

|

My wife and I are not so much independent record producers as we are independent record owners. Besides doing a recording that is every bit as good as ones done by big companies with larger budgets than us, we have to deal with everything ourselves. We have no legal department. We have no licensing department. We have no sales department. We have no distribution department. We have no promotional department And so on. If we don't do it ourselves, it doesn't get done.

Mighty Joe Young |

From finding lost music manuscripts to preparing the music to getting the necessary legalities taken care of to arranging the recording sessions to hiring everybody necessary to get the job done properly, to somehow getting all the needed equipment and information from southern California to eastern Europe (and back again), to researching and writing the liner notes, to putting the final product together in terms of editing, mastering, manufacturing, and then promoting and selling and dealing with royalties and taxes and making sure everyone is thanked properly and gets copies of our CDs, and having to tell radio stations that we can't afford to send them free copies of all our CDs, that's what Kathleen and I do as

an independent record owners. |

| Are people willing to give you advice and pointers and/or lend a hand?

|

That depends entirely upon who you ask and what day you catch them on. A lot of what we learned we had to learn by doing, not by being taught. You study what's out there and try to figure out how to do things. Sometimes you have to pay people for their expertise. And you make lots of mistakes and hope to learn from them. We don't talk much with other film music labels, because they're our competitors, and most of them wouldn't want to give away their secrets to the "competition," and I don't blame them. They had to learn the hard way, so we have to, also.

|

| How long does it take generally to produce one of these albums from inception to final release?

|

We are known as the slowest label on the planet, so there's little valuable information you will get from talking to us about this. I'm sure that other labels can crank things out, but in some cases we're a little like Orson Welles was late in his career. When we have the money to take care of the next step, we then take that next step. If we don't have the money, that step waits until we do.

I spend way too much work researching and writing the liner notes. That's just me. I'm sort of a perfectionist when it comes to things like this, because I know I'm probably the only person who will ever write about such things, so I feel I need to get the job done right. Kathleen and I both had some health problems the past few years, and that was the main reason for some of the delays in getting these last two releases out. |

| Could you describe for us the difficulty of producing an album?

|

It is not necessarily that difficult to produce a film music re-recording, but it is incredibly difficult to do a superb job of producing a film music re-recording. There are also different "levels" of complexity of such albums.

If you're recording the complete score from, say, The Time Machine, then you're probably dealing with only one

music publisher, one composer, and one place where you can find whatever music manuscripts survive. They're either there or they aren't, and the condition of them is probably another constant. If you are lucky enough to have full scores and/or parts, then it's much easier to prepare the music for a performance and recording. If you only have the composer's sketches or conductor's scores (abbreviated versions of the full scores that are similar to the composer's sketches), then the music must be reconstructed so it can be performed by a symphony orchestra, and this takes the project to a much higher degree of difficulty.

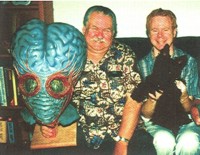

Kathleen, Herman Stein and Schecter in front of the Time Machine

If your goal is the try to reproduce the orchestration used in the film, then you're one step higher in terms of difficulty, because now you can't just make

it sound like orchestral music, you have to make it sound like the exact orchestration that was used on that particular film score. You also have to try to find all the instruments used in the original film, and some of these might be relatively hard to find in Eastern Europe.

Creature From the Black Lagoon |

And then there's another level of complexity having to do with the conductor. If you just want a conductor to do "his take" on the music, then that's much easier than trying to match the conducting style used in the film. Along with the re-orchestration, that's another important factor in determining whether people will find themselves "back in the

film" when they hear the music divorced from the visuals. The tempo, quality of the instruments, dynamics, and other aspects of the performance will either result in you thinking you're listening to the soundtrack you've heard a hundred times in the original films, or it won't.

Then there is one of the toughest aspects of a re-recording, and that is trying to make it "sound" like the original recording, and by "sound" I mean the way the instruments are miked, the amount of reverberation in the recording hall, the engineering, etc. This is in many regards the "missing link" that you don't find in a lot of otherwise-superb

re-recordings. It is VERY hard to do, and more expensive, too, as the orchestra is "naked" because the microphones are set up so they can pick up every last note of every player. The music has a direct, dramatic feel to it that was inherent in the original film's soundtrack, as opposed to a "concert hall" sound that you find in classical recordings--where the music seems to be two parts sound and one part echo.

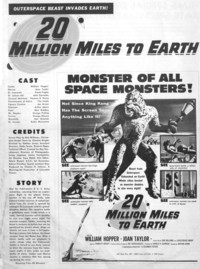

20 Million Years to Earth |

Because of the mike set-up, you not only hear every good note, you hear every bad note, every chair squeak, every sniffle, etc., and this not only makes it tougher to record a good take, the digital editing is harder, too, especially if you have to record a "fix" at a later session. In those cases you have to make sure all the players are sitting in the same positions, the mixing levels are consistent with what you used before, the mikes are set up the same way, and if there was a cricket loose in the hall, you have to find one for the "fix" as well and make sure he's in the same place!

With film music, it is often not so much about the overall sound of the orchestra as it is the relative loudness of a certain instrument or group of instruments, or something that happens musically when there is a combination of instruments playing. We go over every cue well in advance and try to pick out what's most important in each cue-what it

is that makes each piece "special" and memorable. So, while our conductor is rehearsing the orchestra and we're making sure the timing of each cue is getting more and more accurate, we're in the booth with the engineer, letting him know that at bar 8 we need to hear a very bright sound coming from the vibraphone, or at bars 13 - 16, the oboe

needs to go up in volume to a certain level at bar 15, and then quickly back down again. I think this extra step we take regarding the engineering/recording aspect of things is one reason our re-recordings sound the way they do.

And this also gets to the heart of another

matter regarding whether a film score re-recording sounds "authentic." And that is that it must have the drama inherent in the original. A conductor can't just wave his arms while the musicians play their notes correctly. This was not meant to be easy listening music. It was supposed to have passion and energy and vitality, and that is not as easy to achieve as one might think. You almost have to make believe you're at the original scoring sessions summoning up all the energy that was used when the original score was first being recorded. It's easy to tell the difference between a film score that has been performed with drama and one that hasn't. You seem to "feel" the music in the dramatic reading, while you "hear" it in the non-dramatic one.

Kathleen Mayne-music restorer, and Hubert Geschwandtner-recording engineer |

Our goal has always been to try to get everything right. This doesn't mean we succeed 100% of the time with every individual cue, but we come pretty darn close most of the time. For whatever reason, we seem to choose the most difficult music in which to try to accomplish this. Films like Creature From the Black Lagoon, Tarantula, the Tarzan series, 20 Million Miles to Earth and others have multiple composers, music publishers, some of the music came from other films and you have to locate those manuscripts as well. |

Trying to reproduce a "cobbled-together" score so that it doesn't sound "cobbled-together" and so that it makes the listener feel like he or she is sitting behind the conductor at the original scoring sessions is VERY difficult.

Looking back, I'm not even sure how we succeeded as much as we did. Because we have always tried to do the best job possible, from dead-on orchestrations to conducting and playing that seems to mimic the original, to a close-up sound that we feel film music should have. It has always been our goal to make people think they were listening to the

original music tracks, only in crystal-clear, stereo sound. Because of that, there is only one way for our recordings to sound, and while we aren't always 100% perfect, few listeners can detect the differences. My wife Kathleen and I are our own worst critics, as we've lived with this music for so long during its preparation, we know every nook and

cranny of it so that we can try to reproduce that during the recording sessions, where every minute of recording time is costing you more money.

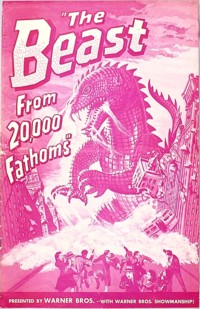

Beast From 20 Thousand Fathoms |

So, the short answer is that it's not that hard to record film music, although it is expensive. But to record it so that all the component parts are at a very high level of quality, that is obviously not as easy to do. If it were, there were be much more of it out there. But it should be mentioned that this is the way WE choose to record film music. There is nothing wrong with recording it so that it sounds like a classical performance rather than a dramatic film performance. There's nothing wrong with a conductor doing his "own take" on something. But that's just not anything we're interested in. Our fans

are fans of the original films, as we are, and they want the music to sound like some long-lost music tracks from those films, not like some other version of the music.

|

| How do you go about deciding what to record? Do you rely on personal preferences, a sort of "please yourself" and others will no doubt be pleased, too, philosophy? Is the historical importance of a score a factor? It would seem that the lack of any recordings or any decent recordings of these scores is an element in choosing. Do requests play any importance in your choices? (If so, I�ve got a few of my own: House of Wax, The Magic Sword, Jack the Giant Killer, Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein.) What future plans do you have? Which scores would you like to record? |

It's a mixture of all of the above. Primary is the fact that the music has not been available in any other format, and we also have to feel that the music is noteworthy. It can be noteworthy for a number of reasons, but most of all, we just have to feel like it's something we want to do. There is so much work involved in recording these albums,

if we haven't chosen something we like, we'd probably never be able to see it through to the end! Sometimes we do something just because we know how difficult it will be, and that if we don't do it, it's doubtful anybody else will. As silly as that sounds, that comes into play more often than you'd think.

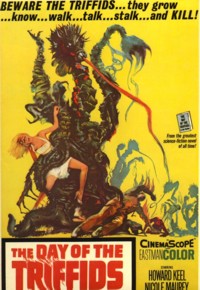

The Day of the Triffids |

I certainly love all the films you mentioned. There are original tracks for Jack the Giant Killer, so maybe one day those can be released. I'm such a fan of Universal's fifties music, so things like Cult of the Cobra, The Incredible Shrinking Man, The Deadly Mantis, and The Land Unknown would be treats for me, especially as I've been friends with many of the composers and their families. I really grew up watching these films over and over, and there's something about them that's just

very rewarding to me.

Believe it or not, the next thing Katy and I are going to do is finish a project we started a dozen years ago! Before we formed Monstrous Movie Music. We came up with an idea for children's adventure stories told with dramatic music that would help kids think creatively-the tentative name is Creative Adventures. As strange as this idea might

sound, it really has more in common with monstrous film music than you would think. We tested it in the L. A. school system and the children went berserk with enjoyment. Maybe it'll get us on Oprah so we can make millions and fund a dozen new MMM projects? Regardless, it will be fun doing a project where I don't need to have anything to do with the movie studios, royalties, and other legalities. It will provide us with a

much-needed break, of sorts.

|

| What difficulties does Kathleen face when trying to reconstruct a score? Is it necessary to work with a composer's estate or family? |

It's only necessary to work with a composer's estate if they possess the music scores or sketches that you need, or if they own the music publishing of that music. Some of the composers and families are wonderful to work with, others are not as pleasurable! But we always try to get the family members as involved as they'd like to be regarding getting us information about the composers so that we can let people know about them, and one of the biggest joys we have is being able to send a released CD to a composer or his family so they can hear the finished product! |

| Has she been able to speak with any of the composers regarding their intentions or how they accomplished a musical effect? |

While Kathleen has spoken to a few of the composers, generally she'll get all the information she needs from the surviving music manuscripts, and by listening to the original music tracks if any happened to survive the ravages of time, and by listening to the film's soundtrack over and over until she's nearly driven crazy by it. Sometimes she has to make educated guesses when music has been changed at the scoring sessions and

what she hears on the film's soundtrack is not what she sees in the sketch or score. She has to try to figure out why the music was changed, what was changed, and then we have to decide whether we'll go with the familiar version in the film that everyone knows, or else go with the composer's original written intent. This usually only has to do with a few seconds or a phrase here or there -- it's never anything like an entire cue is radically different from the film. Oftentimes there's music that was never recorded for the film, and Kathleen has to do her best to orchestrate what she thinks the composer originally

intended, as there's no musical way to "fact check."

A lot of times, composers seem to want to alter their music, now five decades down the line, as they felt they might have rushed things a little when they originally had to compose the music. So it's better to not have their involvement here, as our job is not to change history but to try to reproduce it. Some composers would want 100 musicians playing their music rather than 50, so it would sound "grander" or more like concert music. That's not what our label's about. We have managed to make many wonderful friends through the years via the composers and their families. Long after the CDs have sold their last copies, we will cherish those friendships we've made. A lot of these families think their musical ancestors have been forgotten, and they appreciate the fact that we're trying to let people know what fabulous composers they really were. |

| A composer/soundtrack enthusiast friend of mine(and fan of your recordings) has tried to reconstruct music by listening to the original as it is heard in the film, and comments that the mix in the film often results in a sort of mush in which much of the more delicate and subtle elements of the music are lost. How, in lieu of acetates or original sound elements, does the reconstruction proceed? Do you reconstruct the chord from the pedal point or use the favorite key of that particular composer? There will be inner harmonies that can't be heard, such as when two instruments are paired but one dominates and renders the other indistinguishable. Do

you leave it in anyway just because you know it's supposed to be there? |

Kathleen would be the best to answer this question, but the short answer is that you need to really understand the orchestra, understand the make-up and behavior of the particular orchestra whose music you're trying to duplicate, and go with your best musical instincts. There are many things on the original sketches that you simply can't hear in that "mush" that you mentioned. But you can be fairly confident that if there's a harp glissando in there and you can't hear it, then it should be in there, because it's not like the contract orchestra would have been without a harpist that day. Regarding the voicings, or the "combination sound" you get from two instruments playing together, you just have to make your best guesses based on your musical expertise.

Sometimes you can get clues as to who's playing because you know who played a similar sound in another moment of the score when you were able to pick out the instruments better, or you can figure things out based

on a process of elimination. There's a certain number of players in the orchestra, and if somebody's playing something, he obviously isn't playing something else at the same time! What we always try to get away from is reconstructing a cue from nothing. That is, listening to the film's soundtrack without any manuscripts and trying to guess what every

instrument played and how they played it. This is simply impossible to do accurately. While it's possible for someone to reproduce what they HEAR on the soundtrack, that is usually just a "pale imitation" of what was in the written score. Our goal has never been to reproduce what sounds have survived the ravages of time on a fifty-year-old

soundtrack. It was to reproduce what it must have sounded like fifty years ago when the music was first being performed.

|

| Masatoshi Mitsumoto certainly has an affinity for these scores. Was it hard finding a conductor with a "feel" for these types of scores? |

I think it's hard finding a conductor confident enough in his own talent and ability to be able to check his ego at the door and try not to put his own spin on something, but rather try to match Joe Gershenson's conducting at Universal in 1953 or Ray Heindorf's conducting at Warner Brothers in 1954. I can't picture having a better conductor than

Masatoshi. He was the answer to all our dreams. We knew instantly that he would work out from the moment we first met him, which was at a concert where he was conducting. Katy could tell he had the tools to do the job, and once we got to know him, we realized he had the temperament as well. He grew up on Tokyo as a boy and saw the original Godzilla, so he felt a strong affinity for monsters! I can't overemphasize his

importance enough.

Rear: Herman Stein, Toshi Mitsumoto, Irving Gertz

Front: David Schecter and Kathleen Mayne

|

| Kathleen does a wonderful job conducting Day of the Triffids. |

Recording sessions can be very tiring given our level of "complexity" in trying to reproduce the music the way we do. Masatoshi Mitsumoto had been working so hard to achieve the incredible results he did, and we wanted to give him a little time off to enjoy the sights in Bratislava. Katy loved the TRIFFIDS score so much, so she was very happy to handle the conducting chores. I can't say I was as happy handling her "score reading" chores in the booth, because I am NOT trained to do that! But somehow we managed to record this fabulous music without my botching things up!

Toshi Mitsumoto conducting Radio Symphony Orchestra of Slovakia

|

| Can you discuss the thought process involved when you feel it is necessary to make a musical change that is not present in the original score as heard in the film? |

We usually decide on one versus the other based on how important we think it is to the "fans" of the film versus how important we think the change is musically. In a couple of instances we've recorded things both ways, and then decided to go with one versus the other. These are usually minor changes, but not always.

The Alligator People

The Alligator People |

In the "monster" theme heard in

The Alligator People, the scores did not have that flutter-tongued brass in it that you hear in the soundtrack when you first see the guy with the alligator head stuck on his neck. This music was so important to both the film and also in terms of the musical effect you hear that we had to go with the change. Many times you can tell why they changed

things. You hear it in the recording sessions and think, "Gee, that sounds awful -- I think we'd better go with the change the composer made 50 years ago." A good case in point is in the "Main Title" of Mighty Joe Young. There was some AWFUL orchestration in part of that cue that RKO decided not to go with. We tried it in the studio and it sounded terrible, so that was another easy decision for us to make -- we just did it the alternate way, which was what you hear in the original soundtrack.

|

| Your albums are recorded overseas. There must be problems working in a foreign country. Are there problems in communicating musical ideas to the orchestra? |

I could write a book about it. Think of every possible thing that could go wrong, and multiply by three. Our conductor speaks English and Japanese. The orchestra speaks Polish or Slovakian. Our translator speaks no Japanese, very broken English, but some decent Polish or Slovakian. None of us speak a word of Polish and Slovakian!

So you

manage to communicate with broken English, often through a few players in the orchestra who can speak some of the language. And you use musical language. A good conductor can get his point across in many ways, by humming a few bars, by using Italian, which is where many musical terms come from, and at times we even played the soundtrack over

the recording hall intercom.

I'm sure that is NOT acceptable behavior in the United States, but it worked very well overseas. While a picture can speak a thousand words, a musical example can speak ten thousand! |

| Do you feel that European orchestras have a natural affinity for film music being that so much of the American scoring aesthetic is Old World based? |

No, I think that good musicians who are willing to work hard for you can pull off these things regardless of where they're from. It sometimes takes a little bit of work to get them to understand some of the different ways they're playing certain types of passages from how they're used to doing it, but if they're excellent musicians and the conductor knows what he's doing, I feel you can get a great performance out of anyone. But the musicians have to WANT to do a good job. Our musicians never held back or anything -- they went all-out for us, and you can hear that on our CDs. |

| Are there some amusing behind-the-scenes anecdotes you can share with us? Musical gaffes, instrument problems, etc. |

I would say that musical gaffes and instrument problems do not qualify as amusing. They qualify as "panic time" as we try to figure out how to solve a problem. I do recall one time a bass flute we needed was in Warsaw or someplace other than where we were recording, and we had to shift gears on the fly to record some other things as we were "killing

time" waiting for the train with the bass flute to arrive! One thing we did enjoy was telling the orchestra about the various monsters and the films whose music we were recording. We passed around copies of the movie posters to get the musicians in the right monstrous frame-of-mind. They seemed to really enjoy this. In our Mighty Joe Young liner book you can see a poster of The Animal World on the engineer's mixing board. The musicians and technicians were very interested in the music because so much of it had sounds and instrumentation like they had never heard before, and they wondered what it was in the film that this music was supposed to accompany. |

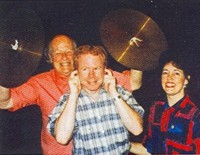

| You had the fantastic idea of recruiting Ray Harryhausen to play cymbals on the Mighty Joe Young suite. The photos in the liner notes with Ray make it look like everyone was having a good time. He's not only a fun-loving guy, but also a great lover of film music, as one might suspect from some of the composers used on his films.

|

Ray had a blast at the recording sessions. He is such a sweetheart to oblige us. He's such a film music fan that I thought he'd get a kick out of playing in a score from one of his pictures. We have a shot of him looking at the cymbal sounds in a music editing program. He really got into the whole thing! I remember at the recording sessions we had

to explain to the percussionist that he would not be playing cymbals on that particular cue ("Beautiful Dreamer") because we were going to overdub somebody else's cymbal clashes later. That was not easy!

Ray clashed his cymbals in the States. One of our mutual friends arranged for a "secret meeting" at one of the movie studios and we did our recordings over there, and later

used Pro Tools to add the proper reverb, placement, etc. to make everything into a seamless whole. The funny thing is, and Ray doesn't know this yet -- when we were doing some "fine-tuning" on a couple of cues from other films, we needed an assist from some of his cymbals all over again, so we re-used them in those places, too! Ray's musical

signature is all over our recordings! |

| I had a discussion with Ray about film scores once upon a time and at that point his favorite was The Fountainhead. He lamented that he and Charles Schneer could never afford Max Steiner. However, he made no mention that a Steiner cue was used in 20 Million Miles To Earth. I wonder if he knew? |

Ray loves Max Steiner, and his score for She and King Kong, of course. There's also a Bette Davis score he loves, but for the life of me I can't recall it right now. Ray had no idea who contributed music to his Columbia scores until I told him it was indeed a bit of Max in there with many others whose music was in Columbia's music library. He was quite pleased to know that a bit of Steiner is in his films, along with Rozsa, Duning, and many others. Ray had hopes at the time of The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms that he could get Steiner to score the film, but the composer was busy at the time. As good as Steiner was, David Buttolph's score is a landmark in monster moviedom, and it's hard to picture a better one. It is so powerful it brought a whole new level of drama to the stop-motion proceedings. |

| One of the aspects of your recordings that make them unique is their acoustic sound. Although you discuss close-miking in your liner notes could you reiterate some of the points that explain why you favor this technique over the usual studio methods which generally produce that cavernous, "classical music" sound? Your technique produces a fully directional stereo sound yet retains the characteristics of a mono mix as in the films. |

Film music is dramatic music, and it just doesn't sound dramatic when it isn't right in front of you. Cavernous sound makes the orchestra seem like it's hundreds of feet away. How scary is a giant tarantula when he's hundreds of feet away? Well, I guess he's still pretty scary, but not as scary as if he's ten feet away! I just think that echo saps the

drama out of the performance -- whether the music is horrific, atmospheric, romantic, or anything else.

Mighty Joe Young |

|

| We truly live in an age of plenty when it comes to soundtrack recordings. Besides the abundance of original soundtrack music being released, more than ever classic soundtrack music is being released. Do you have any advice for your colleagues? |

I would not give any advice to anyone else. God knows we are not getting rich on these recordings, so maybe all of my colleagues ARE! And many of them are producing great recordings. While we'd love to make a ton of money, our first goal has always been to try to do these projects in a very specific way. And that specific way just costs more money and takes more time and effort. That's what we have chosen to do, and if it makes it tougher for us to make back our investment, we can't help that. We're not going to do a less-professional job because it might be more profitable. We do our albums a very specific way -- different from most others -- and one way is not better or worse than

another. I'm sure there are as many devoted fans of the other labels as there are for our label. We each do very different things. |

| Among re-recorded classic film music, both past and present, are there any you admire? |

I love many of the Marco Polo (now Naxos) recordings, like Max Steiner's King Kong, Erich Wolfgang Korngold's The Adventures of Robin Hood, Alfred Newman's and Bernard Herrmann's The Egyptian, and I love Hans Salter's House of Frankenstein. They've done so many great releases. I love RCA's Classic Film Score series conducted by Charles Gerhardt in the seventies. This is a perfect example of film music that was not meant to be 100% historically accurate, but it was performed and conducted with such drama and passion, it recaptures all the excitement of what film music should be about.

Miklos Rozsa did a number of great re-recordings in the seventies as well. While some of these were "concert adaptations" of his film music, they were again vigorously performed and conducted, and are therefore very rewarding.

Fred Steiner is a great conductor, and his Star Trek albums for Varese Sarabande and his Americana film music album (with Bernard Herrmann's The Kentuckian) are as good as you could hope for. There's a lot of great stuff out there, but as with anything, there's a lot of stuff that isn't quite of that caliber. |

| Are you in general a film music enthusiast? Could you name some of your favorites outside the Monstrous Movie Music genre? |

Yes, I love all types of film music. Among my favorite recordings are Herrmann's The Ghost and Mrs. Muir and Elmer Bernstein's To Kill A Mockingbird, which Elmer re-recorded in the mid-seventies. I like them better than the original tracks, and his conducting was exquisite on both. He also did a brilliant job with Herrmann's unreleased score from Torn Curtain. When Elmer revisited To Kill A Mockingbird decades later, I don't think he did as good a job. I also love the Miklos Rozsa

Spellbound compilation in the Classic Film Score series. This was the album that introduced me to Rozsa, and I love every second of that recording. One of these days I'd love to do a complete score recording of The Red House, but until then, there's that glorious Charles Gerhardt-conducted suite. |

| What did you do before albums such as yours were available? Did you make tapes off TV broadcasts? Record from videotape? |

Unlike many of my contemporary movie music fans, I didn't do that. I just tried to catch the films whenever they played on TV. I remember doing audio tapes a few times, but my mother or sister would always come in the room and they'd be making noise and they wrecked the recording! I think I stopped doing that so I wouldn't have to deal with the

frustration of their interruptions! Certainly when video came around I videotaped every movie I could find that I liked, and that I liked the music to. |

| On these two new recordings what are some of your particular favorites? |

I'm really proud of 20 Million Miles To Earth because it was so hard to do, and to do right. I think this is the first time anybody ever re-recorded a library score, and the logistics and complexity of such a project were unbelievable. It's a really fun listening experience, too, as it's a musical conglomeration with original cues holding it all

together. And, of course, Herman Stein's This Island Earth music is a classic as far as I'm concerned. He never got any acclaim for it because there are six cues in the end of the picture composed by Hans Salter and Henry Mancini. But with or without those pieces, this is one of the MAJOR sci-fi scores of all-time, and I'm very happy that we got

it out while Herman was still able to appreciate it. |

| Your liner notes are very impressive works of research, observation and personal insight. Considering their enormous length (40 pages) how long does it take to prepare your comments? |

You forgot to mention all the silly humor. That comes from being a humor writer for about 20 years. Even when I'm being dead serious, I always try to lighten things up a little. It takes me way too long to write these. Of all the things facing me in a possible future MMM project, trying to live up to the reputation we've developed for these

books is the scariest. So little has been discussed about any of this music, there really aren't sources you can "crib" from. You basically have to do every scrap of research yourself, although once you come up with some ideas, that can lead you to some people who might have a document or a distant memory that might help you confirm or deny a

theory. But it's really way too much work, and that's another reason why I'm excited about Creative Adventures -- it's all fiction. I can make everything up! |

| How were the original recordings funded? Are they self-sustaining now? |

Katy and I pay for everything. That is one reason we're so slow. If you know anybody out there who's got millions to throw around and trusts us with some recording projects, please let us know! We could even put their name on the cover, like "Joe Blow presents House of Wax!" Wouldn't that be funny? It doesn't even have to be monster music, as

fans of our recordings know that a lot of the music we recorded was originally written for westerns and adventures and other genres. And we already did Tarzan. Good film music is good regardless of the genre it was written for. Not that we ever expect to hear from any millionaires. I remember sending our discs to Spielberg, not so he'd help us, but just because we thought he'd enjoy hearing what we do. The box of CDs was returned because it was unsolicited! |

| I remember reading somewhere that the Charles Gerhardt Classic Film Score series for RCA cost about $100,000 per album. Is this anywhere in the neighborhood for your recordings? |

As for how much our CDs cost to produce, we don't really know. Besides the actual costs of the orchestra, recording hall, editing, mastering, engineering, printing, pressing, royalties, legalities, and on and on, there's the fact that my wife and I work for free for years on these. That's instead of working for someone who is paying us an actual

salary. When you add our own labor into the equation, these things cost so much that if we had thought too much about it we never would have done it in the first place. |

| These recordings are obviously a labor of love produced for the niche market of soundtracks. Do they provide a living income or is it necessary to carry on with a civilian gig? |

This is very much a niche market within a niche market. We simply can't get rich and retire off these things, and we have to do other work, although much of it is music related, in order to pay for little expenses like health insurance, car payments, etc.! We've had to miss out on a lot of things we would have liked to do and have because we've put so much into our record label. I'm not complaining -- that's just a statement of fact. It's also why we have to sell direct. While we can move a lot more copies getting them to stores and distributors, we're making so little profit on the sale of each one, and these cost so much to produce that the actual profit we get is so much more important than being able to say that we sold this many thousand or that many thousand. We would rather sell two copies where we make a total of $20 profit than six copies for a total of $18 profit. That's why we appreciate each and every one of our customers and try to do the best job possible-so that they're as happy with the results as we are.

Bob Burns and David Schecter |

This is a very tiny market we're working within, and any fluctuation in that market can be the kiss of death for a soundtrack label. Like the other labels, we've felt the hit from people who sell bootlegs of our recordings and "trade" CDRs of our material. In addition, the marketplace has been flooded with so many releases, and many of them in limited-editions. What this has done is turn a market that was originally about the music into one that is as much about perceived monetary value. People buy soundtrack albums thinking they're good investments, and they try to sell them on eBay and elsewhere at ridiculous prices.

Up until now, that seems to have worked somewhat, but I wouldn't be surprise if the speculative market crashes in the very near future. But what it's done is take so many film music fans' spending income away from us and other labels doing good work. I think between the glutted marketplace and the bootlegging/duplicating, sales have probably dropped 50% or more for a lot of labels. That's why we need to reach every last person who might enjoy our recordings, especially as our target audience is growing older, along with us! While there are lots of younger fans who love what we're doing, convincing them to take a chance on music they haven't heard before from films they might not have even heard of, well, that's very difficult.

Once somebody discovers what we do, they usually become very devoted fans and buy all our releases and flood us with requests for lots of other releases, but getting people to take that "risk" is the difficult thing. There's just so much on the market that they might already be familiar with, that's often where their available spending money will go first.

|

| Some purists want only original soundtrack recordings and will not countenance re-recordings. |

It's ridiculous to have a pro-rerecording camp or an anti-one. People should enjoy original tracks and re-recorded tracks because they each bring something important to the table. Music should be a "living" thing -- not just something that belongs in dusty museums. If you know how to bring the music back to life and have the means, then you should do it. To just treat old recordings as "the standard" that cannot ever be matched is ludicrous. Original recording sessions were rushed affairs, and there are all sorts of wrong notes in there.

Many of the composers I've known hated certain performances that are now "locked" with the film. Just because something was done first does not mean it was done best. This is not to put down the original musicians or conductors, because they were the best in the world at what they did. But we're talking about old recordings that are pale reminders of what these brilliant musicians once did. To hear what they REALLY would have sounded like you often need a new re-recording to show all the complexities not audible in the vintage tapes or acetates.

What really bothers me are all these film music "fans" who are so married to original tracks that they seem to spend every waking hour trashing all the labels doing re-recordings, even though they are completely unfamiliar with any of our CDs and those of many of our competitors. They are doing a great disservice to film music by telling

people not to support re-recordings because that will prevent releases of the original tracks. They are so ignorant of the film music business that it is ridiculous, but they are very vocal and extremely annoying. I'm sure we've lost many potential sales because of these people who just like to trash every re-recording every released.

|

| I want to thank you, David, for your candid and detailed responses. I know you're a busy man and want you to know how much I appreciate the time you've given us. |

There were probably a lot of funny things I could have mentioned, but your questions stirred up so many memories -- almost all of them having to do with how hard these projects are to do. Hardly a week goes by when my wife and I don't ask ourselves what the heck we got ourselves into! I know that Katy enjoyed working on the music, conducting it, and supervising the editing as much as anything else she's ever done, so I do hope we get to continue the series, as I'd love her to get more joys from the musical part of things. Maybe one of these days we'll get to record some of her classical pieces, too. She's a great composer with a wonderful melodic sense, something too often

missing from "serious" music. |

I, for one, would love to hear her music. Let's all hope that David and Kathleen get the opportunity to record her compositions for our listening pleasure.

Thanks to David Schecter for supplying all photos appearing in this article. Photos copyright David Schecter.

|

The Alligator People

The Alligator People