| |

|

| |

|

|

The Thunder Child: Bert Coules, radio dramatist

What kind of training did you have? Do they provide radio script writing classes at university? I don't know of any university courses. I never received any formal training as a writer, and I'm not sure it would have helped if I had, since I'm not convinced that "creative writing" can be taught: you can learn things like script layouts and other technical stuff and you get encouragement and so on, but when it comes to the actual content, either you can do it or you can't. For the technical requirements of radio and TV scripts, the BBC used to publish a guidelines book; these days their website has a section called the Writers' Room which has all the information a new writer would need. What was the first script you had produced? The one I mentioned above: a 45 minute drama-documentary called "Wagner in Hell" about the composer's disastrous visit to London in the 1850s. That was in 1977. When your scripts are being produced, are you always at hand in the studio to provide rewrites, or additional material if needed? Yes, I'm always there.

Most of your work has been in the mystery field - Sherlock Holmes and Brother Cadfael. I've done quite a range of mystery and detective stuff: as well as Arthur Conan Doyle and Ellis Peters I've also dramatised works by Ian Rankin, Val McDermid, Simon Brett and others. That's not a deliberate specialisation, it's more of an accident. Yet I see you have developed a science fiction project: Arkship - and for television!

What are your favorite science fiction writers. Sci fi Books? Sci fi Movies? I like the golden age guys: Blish, Clarke, Asimov, Heinlein, Farmer, people like that. I reread the Foundation series recently and enjoyed it immensely all over again. With movies, I'm not so sure: I tend to sit there working out how I would have done them differently. I remember watching the first Star Wars film and wanting to rewrite all the dialogue. You?re a ?jobbing? writer. Do you wait for the BBC to come to you and ask you to write scripts for a particular project, or do you write the scripts and approach them to produce it? A bit of both. They do come to me with projects but I also make suggestions, though I don't write a complete script and send it in: one of the perks of being reasonably well established in a particular field is that you don't have to do that any more. Instead of a full script, I'll write out a proposal, a pitch document, and try to drum up a bit of interest that way. Sometimes it works and they bite; sometimes it gets rejected. A case in point is Anne McCaffrey's Dragonflight which I've been trying to interest the BBC in for donkey's years; I've proposed it a few times but so far no-one's wanted to go with it. I think it would work really well as an audio spectacular: like a blockbuster movie but with no visuals.

It was when pre-recording became the norm that the production process developed into what we have today: like movies and TV plays, radio dramas are usually made scene-by-scene and frequently out of order. There's a lot of physicality, with the actors free to move around inside properly laid-out sets with doors, furniture, props and so on. The main reason for working that way isn't costs, though: rehearse-recording a scene at a time, whether in sequence or not, is simply regarded as a better way to get a good result. It means that productions can be much more complex technically, since the crews can set up each scene individually with different acoustics and microphone placings. Having said that, there can be a budgetary benefit because you can often bring in supporting-part actors just for half a day, say, by scheduling all their scenes together. The general rule of thumb is that we aim to record half-an-hour's worth of material in a day, so a sixty-minute play takes two days, from the first readthrough to the final takes. Then there's the separate post-production process, assembling, editing, adding music and any effects which couldn't be put on in the studio, and generally tweaking and polishing. Also in the States, radio programs usually had a season of 20 or so episodes at a time, whereas in England it seems that five episodes at a time comprise an entire season. Has this also always been the case? Actually, there's no fixed number of episodes. How long a series runs depends on a lot of considerations: subject matter, whether there's more than one writer involved, the overall shape of the schedules, that sort of thing. Again in the States, I don?t think the actors themselves did any of the sound effects - they were always done by specially trained sound effects men. So it was a delight to see in your Holmes recordings that the actors did their own work in that regard. Only sometimes; mostly the effects are done by a member of the technical team who weaves silently in and out of the action like a sort of surreal silent ballet dancer, making the sounds alongside the cast members. There are various reasons why actors occasionally do their own: sometimes the performer can time a sound in with the dialogue more precisely than an effects operator; sometimes the vocal delivery is affected by making the sound while speaking - like hitting someone, or digging a hole, or smashing something; sometimes an actor can feel the performance better if she's handling the props herself. And sometimes, the actor just likes playing with toys. I've been on shows where a cast member had to be tactfully (or not so tactfully) persuaded to let the trained operator do the effects, simply because the actor wasn't very good at it: it might look like simply rattling teacups or whatever, but actually it's a highly-skilled job.

Actually, though, there are quite a few more stations nowadays, including local channels and national digital-only networks. For plays, the most important of these is BBC7 which broadcasts drama and comedy from the Beeb's archives: everything from 1940s sitcoms and sketch shows to big-scale drama series and serials from just a few years ago. What's great is that the entire output is available on the web, which is a superb way for people in other countries to sample BBC radio drama. BBC7 is at [http://www.bbc.co.uk/bbc7]. All the Beeb's radio networks can be heard online now. For your Sherlock Holmes stories, you once stated that the episodes would begin broadcasting on the same day that the cassette tapes of the season would be available in stores. Is this the normal case for any BBC comedy or drama series - or only for specific ones? No, that's pretty common. It's CDs these days, of course, as well as cassettes. In addition, you once said that the basic desire of the BBC was just to air the programs, and that the sale of cassette tapes was, in essence, just gravy. That's changed. The commercial side of the BBC is very important now, though the core activity of the Corporation is still broadcasting. In some ways the BBC isn't one organisation at all, but a lot of separate companies all operating under the same overall banner. Where does the BBC make their money? Advertising during the last 15 minutes after a 45 minute episode? nelWeb Site .htaccess Editor Archive Gateway Disk Usage FTP The BBC doesn't carry any advertising. The broadcasting side - radio as well as television - is wholly funded by the TV Licence, which is a bit like a tax on television sets: every TV owner has to pay an annual fee to the BBC: currently it's just over ?120 - about $220. It's illegal to own a television if you haven't paid: special detector crews in high-tech vans roam the streets, picking up electronic signals from switched-on TVs and checking the owners' addresses against a database to see if they've bought their licence. You have to pay the BBC even if you never watch or listen to any of their channels, a state of affairs which a lot of people don't like; every now and then there are calls for a different system, but they've never amounted to anything. Science Fiction Questions Can you give me a time frame for when each of the productions below aired on BBC? How did you get each ?gig.? 1) The Caves of Steel: Science fiction murder mystery from the novel by Isaac Asimov. That was in 1989 and it was my first SF sale. I proposed it myself: I sent in a pitch document outlining the story and the characters and telling the BBC what a great show it would make, and happily someone agreed with me. I was surprised as well as pleased, because science fiction was a hard sell: the radio drama people didn't believe there was a big enough audience among their usual listenership. 2) A Wizard of Earthsea: Science fantasy from the novel by Ursula Le Guin. They approached me with that one. It started life as a five-part serial for the schools radio department: I wrote the scripts but then it was shelved for some reason - to do with the rights, I think - and shortly after that the producer who had set it up retired. I thought the show was dead but some years later a producer in the main drama department dug it up and wanted to do it as a two-hour one-off, so I got paid all over again to restructure it. It finally went out in 1996.

In doing your adaptions, do you change things from the author?s original story, or do you stay as close as possible to the source material? If you change things, why? Can you elaborate on some specific examples of what you changed in the scripts above and why? (I?m trying to get into your creative process here). You have to change things. A radio play, just like a TV show or a movie, isn't a book, and what works well on the page doesn't necessarily have the same impact if you just transfer it bodily to a different medium. It can actually be false to the original to keep it the same: it does no favours to a novelist or short-story writer to take a moving, exciting and emotional work and turn it into a slow, uninvolving play, but that's exactly what can happen if the dramatisation is too literal or too faithful. It's far more important to preserve the spirit of the original than to reproduce the letter. There's also the point that a lot of novels simply contain too much material to be shoe-horned into a restricted time slot. The Caves of Steel was a ninety-minute drama: a lot of subplots and sidetracks from the book had to be jettisoned. The same with A Wizard of Earthsea at two hours. In fact, though, this is no bad thing: both of those plays would have been incredibly convoluted and hard to follow if I had been given enough running-time to include every element from the books. A dramatisation should distill the essence of the original; it can't cover everything, nor should it. It's hard to recall specific changes, but general examples would include making some supporting male characters into females, both for aural variety and to help the listeners keep track of who's who. I seem to remember changing the details of the climax of The Caves of Steel a bit, because the novel uses a very visual plot-point to solve the mystery: I moved the emphasis over to something more sound-orientated. In Flowers for Algernon the central character keeps a diary - in fact, the entire story consists of his diary entries. I changed the diary into a series of audio recordings made on a personal tape machine, and interspersed them with dramatised scenes which are mentioned or implied in Daniel Keyes' original but which don't actually appear in the story at all. When you're writing new material like that, the challenge of course is to keep it consistent with the stuff that does come more or less straight from the book. Flowers posed a particular problem: if you've read the story you'll know that Charlie Gordon, the central character, goes through some huge changes which are brilliantly depicted by the way his diary entries are written: as he develops, so does his spelling, grammar and punctuation. I had to find a spoken way of reflecting the same journey. You?ve done two non-fiction documentaries about science fiction (a feature on Ray Bradbury for kids, and Spaced Out, a documentary for kids on how to write science fiction: 1) Again, what dates did they air. 2) How did you get the gig. The Bradbury came first, in 1991, with Spaced Out two years later; they were both commissions from the specialist schools radio department, so the programmes had to be basically educational in nature, without being too heavy-handed about it. The schools people came to me with the subjects and asked if I was interested, and when I said yes they left me to tackle them however I felt best. The Bradbury included clips from a superb US LP recording I found of Leonard Nimoy reading extracts from the stories. I was so pleased that we were able to get the rights to use it: professionally speaking, it's the nearest I'm ever likely to get to Star Trek. Television: Arkship: Treatment and storylines for science fiction TV series. When a global experiment to melt the polar icecaps and bring life to the deserts goes catastrophically wrong, the last remaining human beings are trapped aboard the giant zoological space station Gaia One.

People outside the business don't always realise that there's a lot more to casting than just deciding on a name. Actors aren't always available, or sometimes simply aren't interested, or maybe cost too much. I get mail saying "Why didn't you use so-and-so for that part?" as if all we have to do is pick up the phone and that's it. It happens sometimes, but usually it's not that easy. What are the specific technical demands of the medium? Anything more than being able to turn pages quietly! A lot more. A radio actor has to get the whole of the performance into her or his voice: what can be conveyed on stage or film or TV with body-language, movement, gestures or even just a look, all has to be vocalised. It's not easy to do, and it's possible for even a fine actor to go too far and overdo it, or not far enough and end up sounding flat and uninvolved. And then there are specific things like microphone technique: there are many different ways of speaking into a mic according to the exact emotional and dramatic effect you want to produce. Is the BBC financially successful, or are they subsidized by the government? Except for the BBC World Service which broadcasts overseas and is partly funded by the government, there's no subsidy involved at all: the Beeb is independent and self-financing. ?An ideal sound balance for a listener in a car on a motorway would sound very strange for someone in a quiet room with a top-of-the-range audio setup - and vice versa - but the finished programme must satisfy in both situations. Not easy.? You sound very familiar with the technical aspects of getting radio programs recorded. Did you take classes in this bit as well, or did you pick it up ?on the fly?? I worked for several years as an audio technician at the BBC, recording, balancing and editing radio programmes right across the whole range of the output. The training and experience was enormously useful for my writing. What do you have to do in writing your scripts that allow for such sound balance - or do you leave it all up to the technical boffins? Basically I write what I want to hear and leave it to the producer/director and technical crew to achieve it. If they think I'm asking too much or suggesting something that's just not a good idea because it's simply not workable, they let me know about it pretty quickly. Mind you, it's a point of honour with them to try to achieve the impossible on a regular basis, in a limited time and within budget. In general it's my job as a writer to imagine the whole show as I want it to sound, and the script is the way I pass that image onto the people who have to make the programme. So a script is like a music score: it contains all the information about the general soundscape, aural perspectives, sound effects, moves, music and moods, as well as the words the characters say and how I think they should say them. Of course the producer/directors, the technicians and the actors then all contribute their own creative input into the show, and they often bring things to the production which I would never have thought of. There's very, very little that can't be achieved when you're working purely with sound. The great strength of the medium is that it suggests rather than shows: each individual listener is free to imagine the settings, the characters and the action exactly as he or she wants to: as the old clich?as it, the scenery's always better on the radio.

And finally: How about "It's very good of you to answer all these questions - where should I send the cheque?" I hope I've covered everything you wanted. Thanks for asking. Bert Coules, 7th December 2005 All photos and magazine covers retain their original copyright and are shown here as fair use for purposes of reference and review. Thanks to Bert Coules for supplying his photo and one from a Sherlock Holmes radio broadcast. Return to:

|

Recommended Reading

|

| |

To see our animated navigation bars, please download the Flash Player from Adobe.

All text © 2006, 2007 The Thunder Child unless otherwise credited.

All illustrations retain original copyright.

Please contact us with any concerns as to correct attribution.

Any questions, comments or concerns contact The Thunder Child.

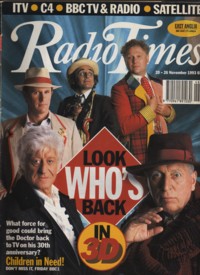

Coules' Sherlock Holmes:

Coules' Sherlock Holmes: