The Thunder ChildScience Fiction and Fantasy |

| |

|

| |

|

|

In a career that ultimately spanned E.C. Comics in the 1950s (Tales From the Crypt, Weird Science); Spiderman and Superman; and the Star Wars comic strip and movie adaptations (fitting, since George Lucas has cited Al's work as inspirational), Williamson left a legacy of spectacular interstellar vistas, and dynamic action. Williamson's greatest influence remained Alex Raymond, and it was Al's love for Flash Gordon that saw him always return to the character, and his fantastic environs, or similarly themed scenarios...

As a four year old, like many kids in 1966, I was entirely captivated by the BatmanTV show. (Between the Batmobile and the parts geek wizardry of Batman's utility belt, there wasn't a dull moment. Each week there Batman had a new gadget that would save the day. One had to realize that not only was Batman a superhero but also a parts geek who could design and build almost anything.) Then, The Green Hornet came along, and there was something equally spellbinding, in a very different way, about ABC's new super hero series. Somehow, I was aware of The Green Hornet record that Al Hirt had put out, with his recording of "Flight of the Bumblebee," the show's theme. (It's likely I caught a Hirt appearance on one of the many afternoon talk shows, then in syndication.)

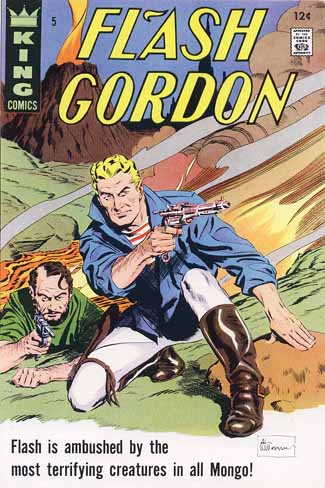

Later that afternoon, she came back with a Flash Gordon record, starring, remarkably, the serials' Buster Crabbe in TWO audio adventures. There was also a spectacular cover painting by someone named Al Williamson. (Leo Records tried something clever that year, also producing a Superman record starring Bob Holliday, who was then on Broadway as the Man of Steel in a musical adaptation, along with some other comics oriented titles.)

In New York, every day on The Beachcomber Bill Show, Bill Biery--a kids TV host, and announcer, whom New York's WPIX had actually imported from Los Angeles, where the show began--would show chapters of the 1930s Flash Gordon serials. In what's really a lost chapter of broadcasting history, the classic adventures were still thrilling new viewers, as late as the dawning of the Flower Power era. If you were a kid, Flash Gordon was as new to you, as that week's latest TV or theatrical offering. And for the first time in Flash'shistory, his adventures were contemporary with mankind's own, actualspace program. (It's entirely likely that one morning, I would watch a NASA Gemini liftoff, and that afternoon, see Flash match wits with the delectable, Princess Aura.) There was also a lovely generational factor. My father had loved Flash''s adventures when he was a boy, seeing them in a lower Manhattan movie house, and we were able to share these thrills across, incredibly, thirty years. Just a short while later, my Dad was delighted when he found a new Flash Gordon comic book on the newsstands, which he brought home as a wonderful surprise. (My Pop, as with many of us, was one of those guys who would scan the magazine and comics racks, to see if there was something neat or unexpected that his son might enjoy.)

I knew, from my Dad, that Alex Raymond had created Flash Gordon. But this was the first time I had seen such detailed, beautiful artwork, inspired by the illustrator's creations. I must have gone over and over that comic--much as I had studied that album--because within just a few years, the cover had separated from its pages, a rarity for the issues in this budding' collector's library. For over the next forty years, Al's visions would never fail to amaze me. Flash Gordon had helped fire my imagination for space adventure, just as it had for Williamson when he was a boy. I can't express the near rapture I had when I encountered Al's lovely work for EC, and all of his other exceptional fantasy and science fiction tales, over the decades to comes. I don't mean to pay short shrift to Williamson's other work. I have several volumes of the Secret Agent Corrigan comic strip that he created with Archie Goodwin (and that was a continuation, so to speak, of Secret Agent X-9, created by Raymond and Dashiell Hammett). And it's intriguing that Al's greatest monetary success may have come as an inker--and a much celebrated one, at that, of course!--for Marvel, and elsewhere, beginning in the 1980s. But it was for his journeys into space that I'll always be grateful. Even just a one page sketch by Al could somehow express the awe that helped inspire so many people whenever they'd think of those far frontiers. If you grew up in the 1960s, you really believed that man would soon have a home in space. Aside from vast budgetary cuts instituted by Richard Nixon in 1969, there was no reason not to believe that NASA's original plan--moon base by the late 1970s, space station somewhere around the same time, man on Mars in 1980, and regular travel to these destinations for ordinary citizens by today--wouldn't come to pass. It was roughly in the 1980s that I realized that this would likely never happen in our lifetime, although--in a great tragedy of non-progress--it could have, had the money been spent... But I was always able to look at Williamson's artwork. It's worth noting, today, how for so many of us, Al gave us the chance to walk through, and indeed, breathe so many alien landscapes. It would be fun one day, when man is finally exploring Mars, and some of our other heavenly bodies, if someone decides to inscribe Al's name on a mountainside, or other landscape. Along with so many other visionaries, of course, the artist had been there first...!

|

|

| |

To see our animated navigation bars, please download the Flash Player from Adobe.

All text © 2006-2014The Thunder Child unless otherwise credited.

All illustrations retain original copyright.

Please contact us with any concerns as to correct attribution.

Any questions, comments or concerns contact The Thunder Child.