| |

The Thunder ChildScience Fiction and Fantasy |

| |

|

| |

|

|

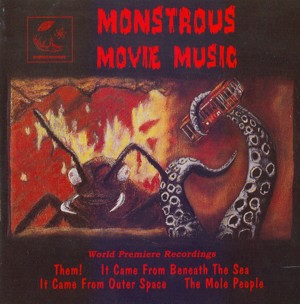

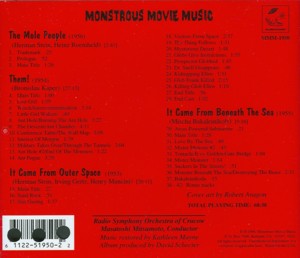

DVD Review: Monstrous Movie Music by Ryan Brennan

The package was marketed under the name Shock Theater and made available for the first time on television some of the most famous of horror films like Frankenstein and Dracula. However, the album was under-orchestrated, wasn't faithful to the original recordings, and belittled the music with jokey introductions and hokey sound effects. One can imagine the enormous challenges facing Schecter and Mayne as they searched for original materials, worked at reconstructing the music, considered the original intent of the composer, compared the written music versus that found in the films, and created their own record company in order to release their album. It's possible that if they'd known how much work would be involved then they might not have done it at all. But they persevered, and we are the lucky recipients, nothing more expected of us than to sit back and enjoy these scores that serve as more than mere nostalgia, but as records of the creative genius of composers like Herman Stein, Heinz Roemheld, Bronislau Kaper, Irving Gertz, Henry Mancini and Mischa Bakaleinikoff. Under the gifted and sensitive baton of conductor Masatoshi Mitsumoto, the music of these men lives again. First up is a short suite of music from The Mole People (1956). The Mole People introduces a lost Sumerian civilization hidden under the surface of the Earth. The albino race rules over the enslaved title characters. Genre stalwart John Agar and Hugh Beaumont (better known as Ward Cleaver on Leave It To Beaver) are caught between the two. The Mole People was a rather late entry in the bid to create another memorable Universal movie monster. The creatures are rather interesting, and there are some frightening moments but even at a relatively short 78 minutes, The Mole People fails to deliver the goods. Of musical interest here is the Main Title, a short piece based on eight measures by Roemheld and extrapolated by Stein that leaves no doubt that horrors are in store for us. Schecter, in his meticulously researched and detailed liner notes (32 pages worth) promises more music from this score in a future release. Them! (1954) was one of the most successful of 1950s science fiction films. Warner Bros. used the same saturation advertising (on radio and TV) and theater booking strategy employed on the earlier The Beast From 20,000 Fathoms (1953) which had resulted in a $5 million hit. The story of giant, mutant ants was treated as a mystery, a still novel approach for this type of story at that time, various authorities, from police, scientists and the military establishment trying to track down and eradicate the deadly menace. The film took itself very seriously and despite what could have turned out as laughable remains one of the most gripping and suspenseful films of its kind. Making no little contribution to the tense tone of the film is the score by Bronislau Kaper. Kaper was a composer equally at home writing a popular song or a significant underscore. Coming off the Oscar success of Lili (1953) was this very atypical genre effort which is handled with same finesse evident in all his other work. Beginning with the Main Title, Kaper immediately amps up the anticipation with a relatively short but dynamic cue, then maintains a mood of mystery as a little girl wanders the desert alone, the police perplexed by the disappearance of her parents and the conundrum of a house trailer and a general store that appear to have been "caved out." Typical of these releases is the inclusion of music excised from the finished films. A particular treat is "Ant Fugue," a piece written to accompany the scene in which a documentary is shown about ants. Recognizing the scene as boring, Kaper wrote a cue to inject some excitement into the proceedings. Mimicking the action of the ants, the reduced orchestral ensemble musically crawls all over itself as woodwinds, trumpets, strings and horns vie for first position only to be pushed aside by another instrument. Dimitri Tiomkin often employed a fugue when a scene lacked real action, writing rising and falling measures packed with musical notes in films like 36 Hours, The Alamo, and High Noon, to name a few. Ultimately, with cuts made to the scene, Kaper's music was dropped, so this recording is a world premiere. It Came From Outer Space (1953) represented Universal's first major foray into the science fiction field and their first film in 3-D, the new process that was thrilling audiences nationwide. 3-D required that viewers wear special polarized glasses that fused together two film images that closely approximated the view from our own eyes. The motion picture screen became a window on another world, creating an illusion of three dimensional depth but also allowing objects to jut or project from the screen into the theater auditorium -- "A Lion in Your Lap!" as the ads claim for Bwana Devil (1952) the first big 3-D hit of the decade. One can imagine the effect of the opening sequence on an audience as a comet sailed straight into the camera and exploded as Herman Stein's "Main Title" boomed out in Stereophonic sound. The craze lasted a couple of years, producing only a handful of memorable movies that stood on their own outside the gimmick. It Came From Outer Space has stood on its own merits and weathered the test of time. Part of its success must be given to Ray Bradbury's story, one that plays with audience expectations and promises to exploit the aliens as a menace to Earth. In the opening of the movie a spacecraft crashes in the Arizona desert. Soon, some of the locals start to act differently, less emotional, as they are taken over by the aliens. That the aliens are eventually revealed as harmless, basically using human bodies in pursuit of repairing their damaged ship, erases none of the previous events that mingle both horror and a sense of wonder.

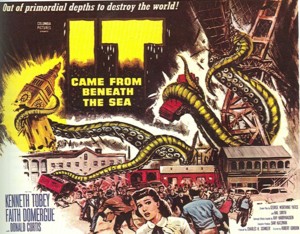

Harryhausen's first few feature films generally took place in urban settings or recognizable locations and did not require the elaborate and beautiful glass paintings and miniature sets that his mentor, Willis O'Brien, had employed to such great effect in The Lost World (1925), King Kong (1933) and other films. Harryhausen's revolutionary methods streamlined O'Brien's techniques, drastically reducing the cost of special effects, yet produced spectacular results. Even so, he could only afford to give his octopus six tentacles instead of eight. But despite the awe-inspiring effects, It Came From Beneath The Sea was noticeably less expensive than Beast. The strict budget also affected the music. Mischa Bakaleinikoff's orchestra sounds thinner than David Buttolph's for Beast. Bakaleinikoff's theme Mister Monster is one of the best known monster themes to genre fans. Its simplicity allowed kids so inclined to mimic the four note theme whenever engaged in play, the notes messaging even the uninitiated that this a monster was on the loose. Typical of this series are the generous liner notes. David Schecter writes with a dynamic sense of the music he is presenting and has a firm grasp on history behind the movies. The 32 pages included here provide fascinating insights into the music and composers, backgrounds on the films and film music in general, and some interesting photos. Cleverly, the releases are numbered for years in the decade of the 1950s. This first album is MMM-1950. The current, fifth album is MMM-1955. Does that mean we can expect only five more albums in the series? That would be sad indeed.

|

|