| The work of the illustrator has generally been demeaned by the serious art establishment. The realistic depiction of toasters, refrigerators, cereal boxes, automobiles or other appliances and products, as well as vignettes taken from short stories, novels, and real life incidents has been, until fairly recently, entirely eliminated from the study of fine art.

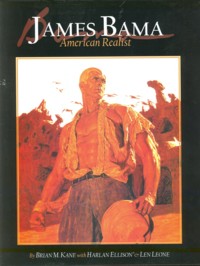

But the realization that art by commission or to serve utilitarian purposes does not negate artistic value has brought some around to the study of artists primarily known as illustrators. One such artist, who eventually moved into fine art, is James Bama. An impressive selection of his work is presented in:

Brian M. Kane's James Bama: American Realist ($34.95; Flesk Publications; 2006; 159 pp). |

|

James Bama |

In contrast to classical painters, who worked from real life and sketches, or who conjured images from the recesses of their imagination, illustrators often found it expedient to work from photos. Perhaps this is one reason the art community is dismissive, but to dismiss the work of illustrators simply because they often worked from photographs is unfair, especially in the case of James Bama.

Bama wasn't just a realist nor a photo-realist. He was a hyper-realist. Many of his paintings are indistinguishable from photographs. His paintings contain a reality so believeable, so authentic, and so human that a viewer may feel it possible to reach into the work. These are not slices of life, they are life itself. No matter how fantastic the subject matter, the paintings are immersive, inviting an onlooker to concentrate their gaze and study the image minutely. |

Bama, a native New Yorker, grew up disadvantaged following his Mother’s stroke and the death of his father. He was already drawing, influenced by Flash Gordon artist Alex Raymond and Hal Foster, creator of Prince Valiant. Following service in WWII, Bama enrolled in The Art Students League. By now his influences were realist artists Norman Rockwell and J.C. Leyendecker, illustrators whose work often graced the cover of the Saturday Evening Post. Not long after, the young artist experienced two important career moments -- he painted his first book cover and the model was Steve Holland.

Steve Holland appeared in the Flash Gordon TV show of the 1950s and served as a Bama model for well over a decade. Most importantly, Holland became the physical embodiment of the artist's most famous and best-loved work, the series of paperback book covers created for Bantam Books reprinting of the Doc Savage pulp novels of the 1930s.

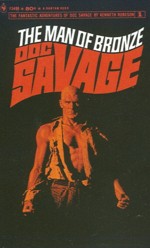

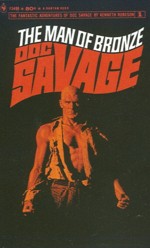

Doc Savage was a super-genius and master sleuth who, along with his five member team, fought crime and solved mysteries. That these were the most exotic adventures, mixing fantasy, horror, and science fiction, was evident from the vivid Bama covers. The first, Doc Savage: The Man of Bronze, featured an appropriately golden hued Doc against a black background, fists clenched in what would become his trademarked torn safari shirt, the artful tears strategically exposing his ripped physique. Anyone who has seen Harrison Ford decked out in a similar manner as Indiana Jones now knows the source of inspiration.

Of the first 67 novels, 62 featured Bama covers in which the artist unforgettably evocatively portrayed Doc amongst some of the strangest flora, fauna, landscape, architecture, and human and inhuman menaces a ten-year old boy could hope to see. Man-size toadstools, pirates, rockets, Vikings, ray-guns, ghost ships, graveyards, submarines, and a variety of spectral images appeared, the seemingly never ending parade of curiosities often favoring a predominant or single color. These books literally grabbed the book buyers attention in the days when paperback books were shelved in racks that fully displayed their covers. These editions are now sought after on the secondary market and considered collectible.

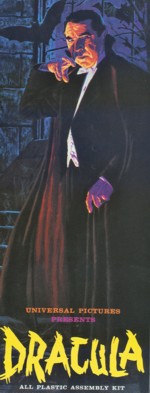

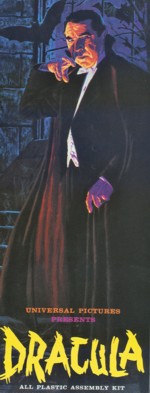

If Bama didn't sear a kid's mind with his images of Doc Savage then he caught them with his atmospheric and colorful box art for the Aurora monster model kits that featured the classic Universal horror icons. Created in response to the "Monster Craze" that began in the late 1950s with the release to television of Universal's classic horror films featuring Frankenstein, Dracula, the Mummy, and the Wolfman, the Aurora plastic kits of the 1960s were a big hit. A huge part of their success was due to the brilliantly realized portraits that adorned their covers.

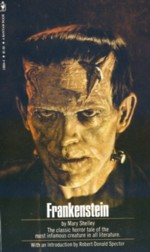

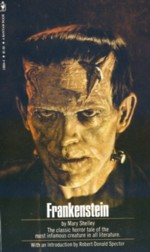

Bama may even have encouraged the literacy of U.S. youth with his eye-catching book covers for paperback editions of Mary Shelley's Frankenstein, featuring a dramatic rendering of Boris Karloff as the Creature, Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, with Frederic March in the most extreme state of transformation, and Jules Verne's 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea utilizing design elements from Disney's film version. The artist was also tapped to provide the cover for the 1960s paperback reprint of the King Kong novelization.

In fact, Bama delivered several hundred paperback book covers throughout the 1960s, primarily for Bantam, his design concepts, from subject, to color, to background literally changing the face of the pocket paper book.

|

Bama's striking covers contributed to the success of early titles by authors like Philip Roth, William Goldman, Anne Tyler, Frank Conroy, and Robert Rimmer. During this same period Bama hit his stride, also creating art for magazines, movie posters, special commissions for NBC and The National Baseball Hall of Fame.

Then, at his height as an illustrator, James Bama retired from the field. But he didn't retire from painting. Able to pick and choose his work, Bama relocated and chose to concentrate primarily on Western art. Now able to command major gallery space, Bama creates spectacular paintings with exquisite detail. Feathers, beads, and fur produce a near tactile effect. His mastery of light is the equal of any painter living or dead.

This volume is profusely illustrated, the layout and design admirably handled. The Doc Savage covers are slightly smaller than their original paperback size but some are given full page treatment minus the print graphics (another publisher plans a separate volume devoted exclusively to the Doc Savage art).

Reference photos employed by Bama demonstrate the extent to which he altered details and infused life into his compositions. The endpapers are a collage of such photos. Noted Science Fiction writer Harlan Ellison and Bantam Books Art Director and Vice-President Len Leone each contribute prefatory remarks. Comments by Evertt Raymond Kinstler, Ray Bradbury, Walt Reed, Boris Vallejo, Dave Stevens, and Jim Steranko, among others, pepper the text. |

If a criticism could be leveled it would be one common to many such books on artists, namely, that the life and career of the artist is treated in an overview rather than detail. Perhaps this is fitting since these are not intended as biographies but celebrations of the art. Bama's frequent, but short, notes on his work are perhaps less important than the silent eloquence of his art. This is a handsome production that should provide hours of repeat browsing. A slipcased, limited edition, signed by Bama, has already sold out.

|

Click on the icons for new features in The Thunder Child.

Radiation Theater: 1950s Sci Fi Movies Discussion Boards

The Sand Rock Sentinel: Ripped From the Headlines of 1950s Sci Fi Films

|

|

|