Travel into Virginia's past with Ghost Guns Virginia

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Support Ghost Guns

|

Yorktown National Cemetery Remembering Fallen Union Soldiers of the Civil War

Please see also the article: Caring for Hallowed Ground

The cemetery is enclosed by a brick wall, and in one corner of the enclosure is a two-story house. A large plaque giving Lincoln's Gettysburg address is affixed to the wall beside the door, but there is no other identification, and the porch door is locked.

If you turn to your left immediately after entering the grounds, and walk along the bushes, you will see a few markers underneath the foliage. There are no weeds around these markers, of course, but still - almost obscured. If you circle the bushes and walk back towards the front of the cemetery, again along the line of these bushes, you'll see two larger monuments, each for a husband and wife.

What is this house? Why are two civilian women buried in a Civil War cemetery? Why do bushes grow over some of the stones? The sign that greets you just as you step into the grounds makes no mention of these things.

Not that I'd expect it to. There is a limit to how much information can be placed on a sign, of course. But, as readers of my articles will soon come to realize, the minutiae of life is a mania to me. I want to know the origin and background of everything there, and I expect people connected with the site to be able to give me this information. And when these people are unable to answer these questions, it puzzles me. Am I the only one to whom these types of questions occur?

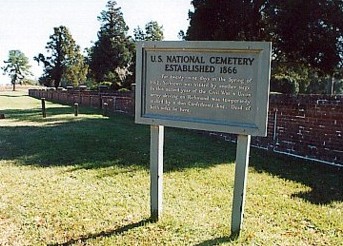

I did come across the photo of a sign at the cemetery, which was not there when I visited on October 26, 2006. This sign clearly was outside the brick wall of the cemetery, identified it, and the text stated:

"For twenty-nine days in the Spring of 1862, Yorktown was visited by another siege. In this second year of the Civil War a Union army driving on Richmond was temporarily stalled by a thin Confederate line. Dead of both sides lie here."

And I wondered - why was this sign taken down? Yes, there's a sign inside the wall, but until you go inside, you don't know what's in there!

In the spring of 1862, war again scarred Yorktown's landscape as a Union Army prepared to besiege Confederate forces holding the town. On the night of 3-4 May, 1862, in the face of Union siege artillery, Confederate forces withdrew from the area. Yorktown then became a Union garrison for most of the Civil War and provided hospital service to sick and wounded soldiers.

By war's end, the remains of approximately 600 Union soldiers had been buried in this area between the 1781 Allied siege lines. In 1866, the cemetery was designated a national cemetery, and Union dead from over fifty field burial sits within 50 miles of Yorktown were re-interred here.

Of the 2,183 burials, two thirds of the remains are unknown. Only 747 are identified.

The soldier on the right is William Scott, also known as the 'Sleeping Sentinel.' On August 31, 1861 he was caught asleep at his post, on picket duty in Washington, DC. He was court-martialed and sentenced to death, but pardoned by President Lincoln. He was killed at the assault on the Confederate troops at Dam No. 1 (south of Yorktown) on April 17, 1862, one of 44 Vermonters killed in that battle.)

The next day I went to the Yorktown Visitor Center, which is owned and operated by the National Park Service, as is the Yorktown National Cemetery. (The Yorktown Victory Center, which you'll see advertised on all the red, white and blue signs along the roads, is a state-owned and operated enterprise.)

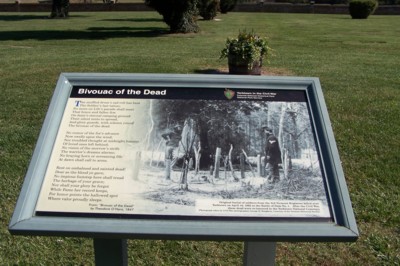

I spoke with a Park official, who could answer some of my questions, but not all. I asked him what had happened to the sign outside the brick wall - he didn't know it was gone, but conjectured it had either been taken down for maintenance or had been removed completely because of the new signs placed inside the grounds. [And now as I type this I remember I forgot to ask him when the Biouvac of the Dead sign [see photo further down in this article] had been placed...but since it's the same design as the Cemetery sign, I'd say it had been put up at the same time.]

The new sign inside the grounds of the house is "about" six months old.

The house in the grounds has been there since 1866, when the cemetery became a National Cemetery. It has been inhabited since that time by a Park Superintendent.

I asked why some of the markers were almost obscured by bushes, and he said they'd been planted that way in 1866, and that's the way they'd been landscaped back then.

I asked him about the women buried in the park, and he conjectured that they were probably the wives of the superintendents who had served there, and been buried there by request. (The cemetry is now closed for further burials, although a small, relatively modern cemetery can be found behind the brick wall.)

The official did not mention any other women there, but, he did give me a handout which consisted of 1/2 page of information and a 20-page list of the names.

Right: The markers for the two men whose stories are told on the sign at the front of the cemetery.

This handout the official gave me had some very interesting information, which I had not seen on any of the websites I had visited.

In an inspection made in 1868, it was reported that :

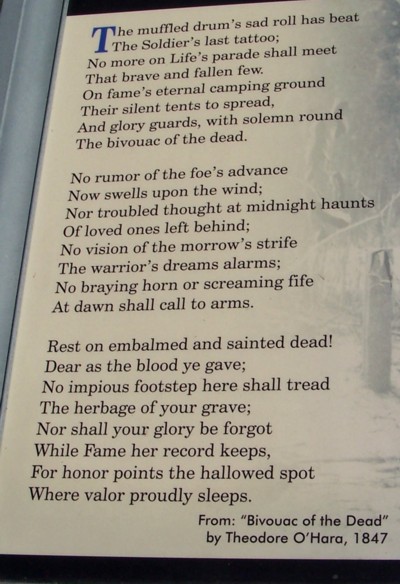

Theodore O'Hara, a Confederate colonel, wrote the "Biouvaco of the Dead" poem in 1847, in honor of the Second Kentucky Regiment officers who died in the Battle of Buena Vista in February 1847, during the Mexican-American war (in which many of the Civil War officers had gotten their first real experience of war.)

The handout given to me by the official also stated that "10 Confederate soldiers and three wives are also identified." But, the source for this piece of information is not given, it's just stated. There are 1,596 marked graves in the cemetery, but a total of 2,183 burials. (Several of the markers speak of "3 Unknown Soldiers," or "2 Unknown Soldiers," in other words the men were buried in the same grave.

Maintaining the Yorktown National Cemetery is a never-ending task, and has sometimes been made difficult by the forces of nature. Hurricane Isabel hit on September 13, 2003, and caused the flooding of some part of the cemetery, such that the remains of seven soldiers were uncovered.

On Memorial Day, 2004, the men were reburied, with the assistance of a group of Confederate re-enactors, who provided donations to build caskets modeled on those made in 1866, and and assisted in their burial. ("Confederate group assists in reburial of Union soldiers" Richmond (VA) Times-Dispatch, 27 May 2004, written by Andrew Petofsky).

|

Photo by Kim Denny. Reproduced with permission

Photo by Kim Denny. Reproduced with permission