The Conrad Veidt Society

With Elisabeth Bergner in “Nju” (1924)

After the show we would go to a cafe, and drink coffee and look into each others

eyes. I thought life held nothing greater, more poignant, than those moments. Then

I would take her home in the train and we would walk through the forest. Have you

ever walked late at night through a forest when you are first in love? It was the

Spring, the nights were tender and exquisite. We vowed we would love each other

forever. I took her home, resented the parting, and had to walk back through the

forest alone. That was in early 1914, that time so long ago, it seems, when the

whole of Europe went up in flames. I was a soldier, of course, but I was weak and

delicate in those days. Within six months I had been invalided out of the army,

and drafted to a place called Libau, behind the Russian front. There was a theatre

there, with a very good little stage, and the authorities had established a sort

of repertory company for the troops. I believe we were pretty good. We did everything,

Shakespeare and others -

In 1916 I was sent back to Berlin to the Reinhardt Theatre, I began to play

small parts. My will to succeed was never stronger within me. It was a kind of urgent

drive which forced me forward, the impetus gathering strength as it progressed. Too

many people, I feel, think to themselves, "Oh. well, I've got a good job. I haven't

done what I want to, but life's too hard to struggle against. I'll rest on my laurels."

That I have always refused to do. For me, half the joy of achieving has been the

struggle and the fight, the pitting myself against the world and all its competition

-

That was way back in 1917, and this critic, a true man of the theatre, resented the films, felt they did not contribute anything to art and beauty. That was the beginning. I stayed in the Reinhardt Theatre, gradually becoming a star, playing bigger parts each time. I was working with the greatest actors and actresses of my time learning something from one, something from another, moving with greatness or potential greatness, and perfecting my technique in the inspired atmosphere of that theatre with Max Reinhardt's personality dominating our lives and our work.

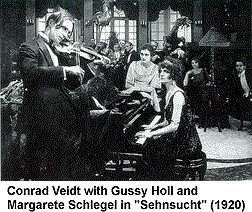

Conrad Veidt and Gussy Holl

Conrad Veidt and Gussy Holl

Since my first love I had been too much absorbed in my art to pay very much attention

to women. I had never been, never could be, indifferent to them. There were one

or two gay functions, just the usual relationships between colleagues working together

in the highly emotional and inspiring atmosphere of that theatre. Until I met the

woman who was to be my first wife. That picture is very clear in my mind. It was

one morning after a matinee performance, an opening in which I had for the first

time played a leading part. I walked out into the sunshine, and there were the usual

group of people standing talking in the square outside the theatre. There was high,

excited talk of the theatre, quick bursts of laughter, flattery, superlatives. I

drew deep breaths of this atmosphere. I was feeling grand. The world was mine.

I greeted friends and acquaintances. I looked around. Outstanding in that group

was a tall, beautiful woman. What do they say in love stories? Their eyes met.

Ours did. It was like a physical impact, something vital and quick, happening to

us both. And I knew, from that moment, that whatever happened between us, we might

disagree, get on each others' nerves, quarrel, do each other harm, but we could never

be indifferent. Actually there was no question of disagreeing. We met, we agreed,

never got on each others' nerves, never quarreled, never did each other harm, and

fell desperately, absolutely in love. I must explain that at that time she was a

famous personality in Berlin. She was a brilliant 'chanteuse', perhaps the best-

After my mother died, I found, a little book of hers which recorded everything

I had ever done, how I had done it, and how proud she was of her son Conrad. I have

tried to tell in some way what my mother and I meant to each other. It is hard to

express precisely what the bond was that existed between us. It was not that my

mothers' love was unduly possessive, nor that I deferred unduly to her wishes. It

was a bond which, when she died became infinitely stronger in an intangible form.

It affected my relations with my wife, as it did every contact I had with the material

world. Now, with a measure of detachment, I can see that I was possessed of what

the psychologists would call the mother-

The Story of Conrad Veidt

SUNDAY DISPATCH, OCTOBER 1934

(Continued)