The Conrad Veidt Society

In the end, the student lies dying near his shattered mirror image and on his headstone is placed the epitaph, "He played with the Devil and lost!" The story was later remade in another version, but the Veidt version still stands as the most definitive and a classic of silent cinema.

By September 1926, Conrad was finally free to go America to take John Barrymore

up on his offer to make THE BELOVED ROGUE (1926). The Veidt family arrived in New

York on September 24, 1926. They then boarded a train for a four day journey to

Hollywood, which afforded Conrad a well-

Upon his arrival in Hollywood, Conrad was met at the train station by Barrymore

himself, in make- An amusing anecdote about Veidt’s arrival in Hollywood is

recounted in Scott Eyman’s Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise. Shortly after Veidt

and his family arrived in Hollywood, famed director Lubitsch took Conrad to see a

boxing match. Soon, the match had slowed down due to the half-

An amusing anecdote about Veidt’s arrival in Hollywood is

recounted in Scott Eyman’s Ernst Lubitsch: Laughter in Paradise. Shortly after Veidt

and his family arrived in Hollywood, famed director Lubitsch took Conrad to see a

boxing match. Soon, the match had slowed down due to the half-

Initially, Veidt had thought he would only be in town to make one film; but the Veidts ended up staying in Hollywood for two and a half years and Conrad would a make a total of four films before returning to Berlin. Two of the films would become classics and two would be routine outings.

The first major success was THE BELOVED ROGUE (1927). Produced by Universal,

THE BELOVED ROGUE was a period piece set in medieval France and pitted legendary

Robin Hood-

After the success of BELOVED ROGUE, Conrad was signed to a contract by Universal

and appeared in three more films. The first, A MAN'S PAST (1927) co-

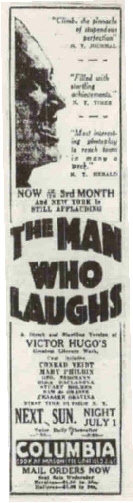

Based on the famous story of the same name by Victor Hugo, THE MAN WHO LAUGHS starred

Conrad as a hapless young nobleman, Gwynplaine, who is ordered disfigured by King

James II. A band of Gypsies is paid to carry out the sentence, carving a terrible,

permanent smile on the young man's face.

Based on the famous story of the same name by Victor Hugo, THE MAN WHO LAUGHS starred

Conrad as a hapless young nobleman, Gwynplaine, who is ordered disfigured by King

James II. A band of Gypsies is paid to carry out the sentence, carving a terrible,

permanent smile on the young man's face.

The make-

The second effect that THE MAN WHO LAUGHS had was to inspire comic book creator

Robert Kane. Kane had seen THE MAN WHO LAUGHS and when he later created Batman comics,

he created a character inspired by Veidt's performance, the now-

Veidt's last role before leaving America to return to Germany was named, aptly

enough, THE LAST PERFORMANCE (1929). The film co-

By the time Conrad Veidt's stay in America was nearing its end, full length, sound films were beginning to appear. In the milieu of the silent film, Veidt the pantomime master was completely at home, and an international star, owing to the universal viewability of silents.

The imminent arrival of sound films greatly concerned Conrad, but ironically, he would encounter little difficulty in the new medium, as his speaking voice was superb, and he would be able to improve his English. What remained of his German accent would only add to his charisma as an actor.

In fact, Conrad Veidt would always be known as one of the few actors who was so consummately skilled and professional that he rarely if ever needed coaching or other assistance with his lines.

An amusing and interesting anecdote from Veidt's own life says something about perception and silent films. One day in 1928, when Viola was three years old, Conrad took her to see her first silent film, a western.

After watching for a while, Viola tugged on her father's sleeve and said, "Tell me, Papa, why do they speak so softly? I can't hear what they are saying." Veidt gently explained to his daughter why there was no sound with the film, but Viola had trouble understanding how there could be so much action, so many fierce expressions and gestures, and no audible sound.

In the annals of film history, one thing is certain. During the silent days, audiences "heard" Conrad Veidt. His artistry on the screen bridged the gap of silence.

Also about the time that Conrad was preparing to leave for Germany, discussions started at Universal regarding the proposed production of a new film called DRACULA (1931). Carl Laemmle, the head of the studio, heavily favored casting Conrad Veidt in the title role. But the actor was reluctant to tackle sound films in English and felt that, with the advent of this new medium, he would fare better in his native Germany.

No agreement could be reached and subsequently, an unknown Hungarian actor named Bela Lugosi would be cast in the part. Although Lugosi is now legend, one wonders what sort of eerie portrayal Veidt would have conjured up in the role of Dracula.

In February 1929, Conrad Veidt and his family left for Germany. Interestingly, Conrad wasn't the only member of Hollywood's German colony leaving for Europe. Such luminaries as Emil Jannings and Pola Negri were returning to their homeland to cope with the new sound medium in their native language.

Ironically, many of them, Conrad included, would leave Germany again within just a few years due to the rise of the Third Reich.

Shortly after his return to Germany, Conrad had the opportunity to appear at the German premiere of THE MAN WHO LAUGHS, at the Universum Theater on Kurfurstendamm on March 1, 1929. The film was as well received in Berlin as it had been in the United States.

That same month, a "Welcome Back" party was given for Conrad by an old friend. The party was attended by many German celebrities of the day, including from the world of stage and screen, and was a resounding success for Conrad.

For the next four years, Veidt worked steadily in an average of four films per year, making a number of memorable films including WIR IN HOLLYWOOD (1929)(a documentary), DER KONGRESS TANZT (The Congress Dances) (1931), RASPUTIN (1932), and FP1 DOESN'T ANSWER (1932).

By the early thirties, Veidt's marriage to Felicitas had disintegrated, leading to their amicable divorce in 1932. Also, the rising power of the Nazis made life ever more intolerable for Conrad in Germany. So by the end of 1932, with his marriage to Felicitas over and the political situation in Germany deteriorating, Conrad knew that he must leave his beloved Germany soon.

Also, embittered by the failure of his marriage to Felicitas, Conrad had sworn to himself in exasperation "Never Again" in the matter of marriage. But in short order, Conrad met an attractive and vivacious young woman who managed a cabaret in Berlin which he regularly visited, and in spite of his vow to himself to "never again" marry, Conrad Veidt and Ilona Barta Prager ("Lily" to her friends) were married on March 30, 1933, forming a union that would last for the rest of Veidt's life.

In May 1933, Conrad and his bride departed Germany and took up residence in England.

In the preceding months, Veidt had to make numerous and complicated arrangements

for the move to England and was hampered greatly by increasing monitoring of day-

Although he had been awarded custody of his daughter Viola by the Court, Conrad

made the difficult but wise decision to give custody of Viola to his ex-

Thus, Felicitas and Viola were comfortably ensconced in a home on Kaiserdamm street

in Berlin, where they remained until 1935, when Veidt moved them to a safe home in

neutral Switzerland. This was done because finally Conrad had found out that Viola

was to be involuntarily inducted into the Nazi-

Conrad Veidt:

The Cinema's Master

of the Shadows

(Continued)