The Conrad Veidt Society

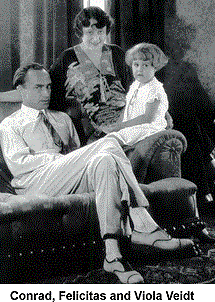

There occurred now the second big thing in my life. After three years of happy marriage,

my daughter Viola Vera Maria was born. An emotion, the tenderest I had ever yet

experienced, surged over me. This was complete, perfect happiness. The coming of

Viola made me whole again. Do not ask me how I behaved when my daughter was born.

Like a crazy man. Certainly I did not comport myself like a normal father. You

might have thought nobody had ever had a baby before. I wanted to do the craziest,

the most extravagant, the most useless things. When Viola was a year old, we all

went to Travemunde for a lovely lazy holiday. Viola was enchantingly interesting;

she and my wife and I laughed and played, three children together. Into this sunshinely

happiness there came a telegram from the United Artists office in Berlin. "Would

you like to come to Hollywood and play in a picture?" I wired back for some details.

This telegram flashed back to me: "I saw your picture 'Waxworks'. You must play

in my picture. King Louis XI. I cannot make the picture without you. -

There occurred now the second big thing in my life. After three years of happy marriage,

my daughter Viola Vera Maria was born. An emotion, the tenderest I had ever yet

experienced, surged over me. This was complete, perfect happiness. The coming of

Viola made me whole again. Do not ask me how I behaved when my daughter was born.

Like a crazy man. Certainly I did not comport myself like a normal father. You

might have thought nobody had ever had a baby before. I wanted to do the craziest,

the most extravagant, the most useless things. When Viola was a year old, we all

went to Travemunde for a lovely lazy holiday. Viola was enchantingly interesting;

she and my wife and I laughed and played, three children together. Into this sunshinely

happiness there came a telegram from the United Artists office in Berlin. "Would

you like to come to Hollywood and play in a picture?" I wired back for some details.

This telegram flashed back to me: "I saw your picture 'Waxworks'. You must play

in my picture. King Louis XI. I cannot make the picture without you. -

(The Veidt Family )

I will not deny that I was impressed and touched. I knew of John Barrymore

as a distinguished stage actor already squiring a big Hollywood reputation. But

I was happy there in the holiday sunshine with my wife and Viola; the whole of life

was spread out before me; there were no worries; my future in Germany was assured

anyhow. I had a curiously superstitious feeling. If I go away now and accept this

offer, it may shatter this happiness. Live in these moments, Conrad; they may never

return. Another telegram came : "You must sail in two weeks. -

When I first saw New York I thought, "Ah, now I am playing in 'Caligari' again.''

It was the same hectic, strange loveliness, an expressionist dream. Lothar Mendes

came to meet me and look after me in New York for the two days I was there. I had

known him at the Deutsches Theatre, a perfectly charming young man, an actor in those

days, and a good actor. Well, it was like home having him greet me in New York;

we had a couple of grand days together. Then came an 86-

I went, of course, as all new importations from abroad go, to the Ambassadors. There you could stay in the hotel and be part of it, or, if you preferred it, you lived in a bungalow, with a courtyard and gardens, and a swimming pool and every Hollywood comfort, which means plenty, plus the hotel service. There was a bungalow awaiting me, all ready to hang up my hat. It was prohibition time, of course, but there was a nice sight on the table. A bottle of champagne. There was an important opening that night, a double event, a big new film starting in a big new theatre. They said, of course, I must go. Barrymore had arranged it. But my big trunks had not arrived, so I had no dress clothes, and of course, in Hollywood there is no laxity about dress. Openings are formal. They said, "We'll hire some." We decided against a tail suit, because that has to fit superbly, and I seemed to be a few sizes higher and larger than most of the men around there. Well, they found me a tuxedo, and I put it on, and I said "No, thank you, I will not go to the opening." It was short in the arms and tight under the arms, it creased when I moved; the trousers were like armour. I looked terrible. But they said: "It does not matter. It does not look so bad as you imagine. You must go. John would be too disappointed if you didn't." So I went to the opening. It was the typical Hollywood opening that you have read about. Crowds of fans lined up outside the theatre to watch the stars go in. Searchlights followed your movements from car to door. To me it was astonishing, vital, and exciting. We had openings in Berlin, but nothing like this. I was nervous, of course, as it was my first public appearance and I wanted to make a good impression, but can you make a good impression as a dignified dramatic actor in trousers three inches too short? One by one the stars made their gracious way down the aisle. Then they announced "Now here is Mr. John Barrymore and the great German actor, Mr. Conrad Veidt." The crowd cheered, I took one look around me, another look at my dress suit, jumped from the car, and ran down the aisle like a hunted man. John, charmingly understanding, ran behind me. As I ran I heard applause and whistles. I thought they were booing me, laughing at me. But I learned afterwards they were applauding.

The film I made with Barrymore was "The Beloved Rogue", Alan Crosland directing. Barrymore, of course, was the star, but nobody could have been kinder, nicer or more generous to a stranger. When the picture was shown I was away from Hollywood, and John sent me a telegram embodying many of the critical ravings about my performance, saying, "You have stolen the Beloved Vagabond from your beloved John." I wish I could have known him better during my time in Hollywood, but possibly, because I could not yet speak English, I did not get acquainted with many of the American actors and actresses there. Hard work on the picture, and the business of getting into the rhythm of a new life, helped me forget the bitterness of being parted from my wife and Viola. Before I had finished the film I had three offers. I accepted

Universal's..... After six weeks in Hollywood I went back to Germany to spend

Christmas with Mrs. Veidt and Viola. Then I brought them back with me, for better

or worse, to Hollywood. It was a stormy crossing, but Viola swayed with the boat

and seemed to enjoy the rough weather. We stayed one week in my hotel, then Mrs.

Veidt and I wanted a house. We took a Hollywood house in Camden Drive; I can remember

the name today. My neighbour was Norman Kerry, a very good actor-

The Story of Conrad Veidt

SUNDAY DISPATCH, OCTOBER 1934

(Continued)